This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity, and organized around key phrases in the conversation.

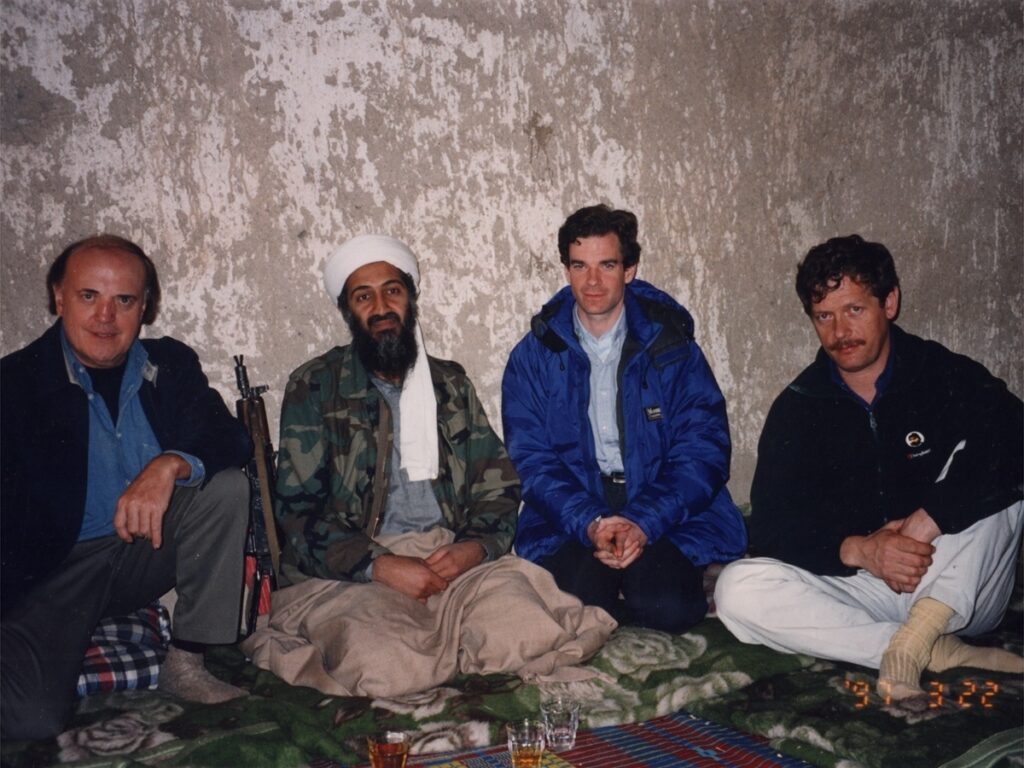

Interviewing Osama bin Laden

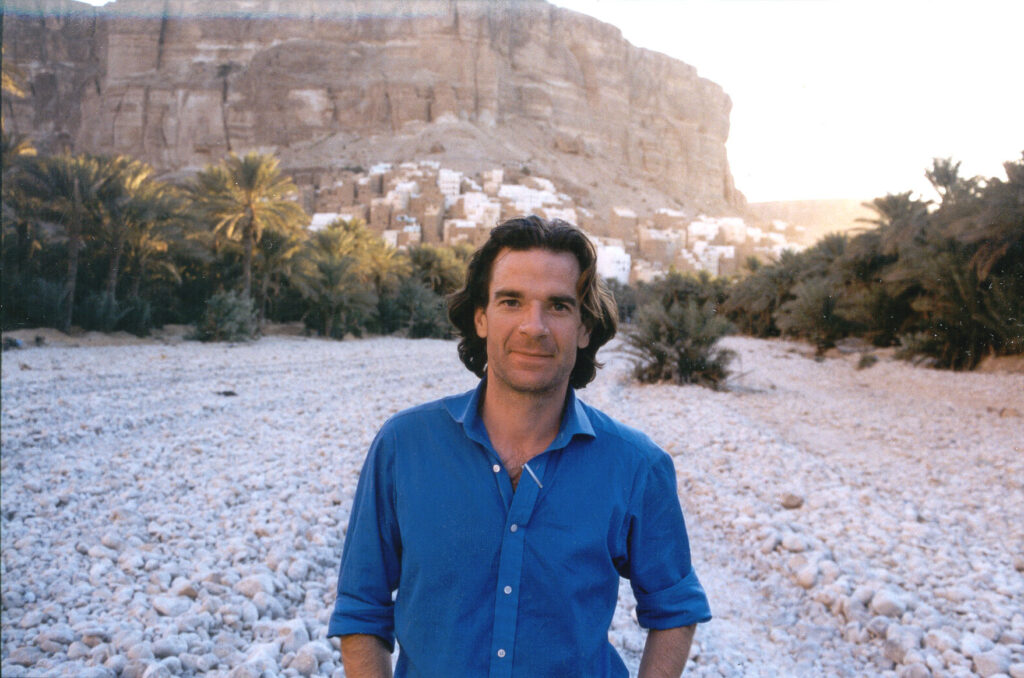

I was dogged about following that story because of my long-held interest in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region.

I first went to Pakistan in 1983 as a university student with two friends to make a documentary about the Afghan refugees fleeing the Soviet invasion of their country. To be clear, we knew nothing about filmmaking, or much about these two places, but we were all aged 20, so we just went for it. And ultimately, the film, Refugees of Faith, was shown on Channel 4 on British TV. I didn’t know it at the time, but that was the beginning of my career covering the region.

In the mid-1990s, I was working as a producer for CNN, and I asked my bosses if I could travel to Afghanistan and try to secure an interview with Osama bin Laden. To their credit—given the expense and danger of such a trip—they said yes. I owe a lot to them for giving me that green light. Bin Laden was, at the time, threatening to attack the United States, and I wondered how one could attack the most powerful nation on Earth from a mud hut in Afghanistan?

I was 34 years old when we interviewed bin Laden. The reason I was able to get that interview was that, by that point, I had developed something called patience, which wasn’t something I had when I was younger. I spent weeks and weeks with people who were bin Laden’s associates—these were mostly Syrian or Saudi dissidents. These guys were very paranoid and not used to dealing with the media. I spent much of my time trying to persuade these men that the interview we could conduct with bin Laden would be no different than an interview with anybody else.

Around that time, al-Qaeda had declared war on the U.S. in one of the few independent Arabic newspapers, and no one had really noticed. So, I think that bin Laden wanted to do an interview with a Western media outlet to declare war because, in his particular brand of jihadism, he had a duty to warn. He wanted to lay a predicate that he’d warned America before an attack.

Interviewing bin Laden certainly sent me down a particular career path.

Osama bin Laden’s compound

I was the first and only journalist granted permission to enter Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, where he was killed, and where he had lived the last few years of his life. I didn’t know that two weeks later the Pakistani government would demolish the place so that it wouldn’t become a shrine to bin Laden.

The whole place was completely undisturbed from the 2011 raid by the U.S. Navy SEALs. There were broken glass windows and blood splatter on the wall from bin Laden’s killing. Cows were in the pasture, and crops were growing in the yard—ensuring that bin Laden and his family never had to leave the compound; they could be self-sustaining.

Some of what I found demonstrated bin Laden’s vanity—a box of “Just for Men” hair dye, something he used in the final years of his life to dye his hair and beard jet black because they had otherwise gone white. I also noticed Avena syrup, a purportedly natural form of Viagra—bin Laden was against the use of pharmaceuticals. Although he seemed much older than he was at the time of death—54—he was only middle-aged. And he had four wives who ranged in age between their mid-20s to early 60s.

There was also a treasure trove of documents recovered by the SEALs. And I love documents because they largely don’t lie. These materials have helped me understand his relationship with his wives and family. I found a very tender letter he wrote to his oldest wife, whom he hadn’t seen in 10 years because she was exiled in Iran. She had a PhD and played an instrumental role in writing his speeches.

Because he was taking every precaution possible, bin Laden never thought he’d be found. As a result, the documents found at the Abbottabad compound represent his true views and what was on his mind at that time.

Humility

I was friends with the war photographer Tim Hetherington, who was killed more than 10 years ago by a rocket while covering the Libyan revolution. He was an amazing person. In fact, my wife and I named our son, Pierre Timothy Bergen, after him.

On the tenth anniversary of Tim’s death, I wrote an op-ed continuing to marvel at his humility, saying “Tim lived and worked in the toughest environments in the world, from Liberia to Afghanistan, to Libya…but he was never jaded by those experiences, nor was he a showboat about his many years on the front lines. He was a very gentle man. A gentleman.”

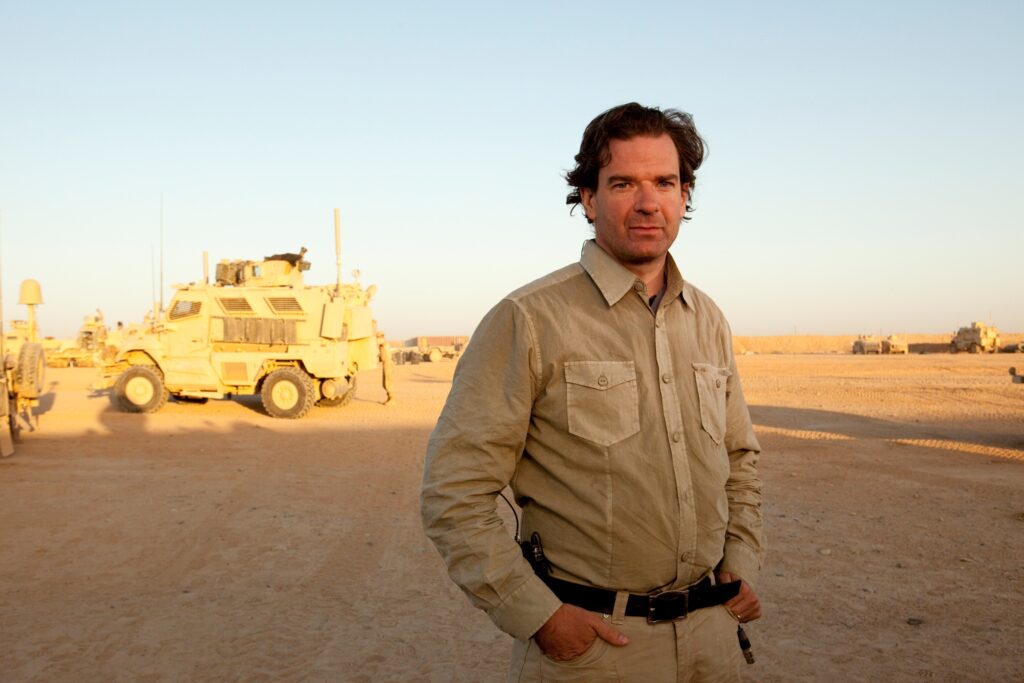

Tim and I met on a CNN reporting trip to Afghanistan that I was producing with Anderson Cooper and Tim was taking still photography. We were embedded in a Marine base in Nawa, Helmand Province, the kind of place that had no water or electricity. And yet, Tim loved it, just like he loved Afghanistan. He was very low-ego and a real artist. His film, Restrepo, is one of the best war films ever made.

After that trip, we stayed in touch, and he would visit and stay at my home in Washington. Everyone who knew him loved him. He was such a thoughtful human being.

Becoming a podcaster

Starting the podcast In the Room with Peter Bergen, I didn’t know what I didn’t know. Look, anybody can create a podcast, but to produce one that people actually want to listen to, and one that has structure, narrative, and drama, well, that requires some skill. I was so fortunate to have as our executive producer Alison Craiglow, who formerly ran the Freakonomics podcast and public radio show. We also had a team of really good producers, assistant producers, and a sound designer. And we produced the entire show virtually because we were all spread out from Brooklyn to Washington, DC to Mexico City to California to Chicago.

I find that audio allows people to let their guard down in a way that they wouldn’t if they’re on camera. And the barriers to entry are much lower in terms of cost. I enjoyed it a great deal and I learned a lot about audio storytelling.

The “War on Terror” era

I’m writing a book about the history of the war on terror from September 11 to the withdrawal from Afghanistan. I told my friend Vali Nasr, a former senior advisor to Richard Holbrooke on Afghanistan and Pakistan, about the premise of this book, and he said that he thinks now is the right time to tell this story. That’s because enough time has passed—we are far enough away from that era in history to take a look at it.

The global war on terror is as much an epoch as the Cold War was. It was a distinct era in American life. And there is now a treasure trove of material available to the public about that period. The Miller Center at the University of Virginia, for example, interviewed all of the principals from the Bush administration back in 2012 and publicly released the transcripts in 2019. Similarly, Southern Methodist University conducted interviews with all of the people involved in the surge decision in Iraq, offering another informational gold mine. So it’s exciting to explore these kinds of materials.

This is my eighth book, and there are a lot of traps a writer can easily fall into—and I’ve done them all by this point. I used to think that I had to know absolutely everything there was to know about a subject before writing anything. Well, that’s just not possible. I also used to think that I had to put everything I learned into a book, but if I did that, it would be an encyclopedia! Now, I find that writing a book is as much about what you leave out as what you keep in. There has to be an understanding of narrative and a sense of where to begin and end the story.

How Washington, DC has changed

I moved from New York City to Washington, DC in the early 1990s when it was the most dangerous city in the United States. It has since become much safer and has gained roughly 200,000 more people. I’ve also watched another shift take place. People used to move to DC temporarily to work for an incoming Administration and then return to wherever they came from once that term ended. Now people come here for those kinds of jobs, get married to someone who’s like-minded, and stay put.

I continue to live here because I’m interested in history and national security, and this is where the sausage gets made. It’s not being made in London, Paris, or any other American city; it’s made here, and I think it’s a really interesting place.

During this second Trump administration, several of our friends have lost their jobs or their professional sectors have been turned upside down. For that reason, it’s a strange place to be right now; there’s a great deal of uncertainty. But I think our political system will right itself quicker than people might think.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.