Vann R. Newkirk II wakes before dawn in a small apartment overlooking the Alabama River. Outside his window looms the dark outline of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where in 1965 officers beat and tear gassed hundreds of civil rights marchers. In Selma, Alabama, history has a way of engulfing you.

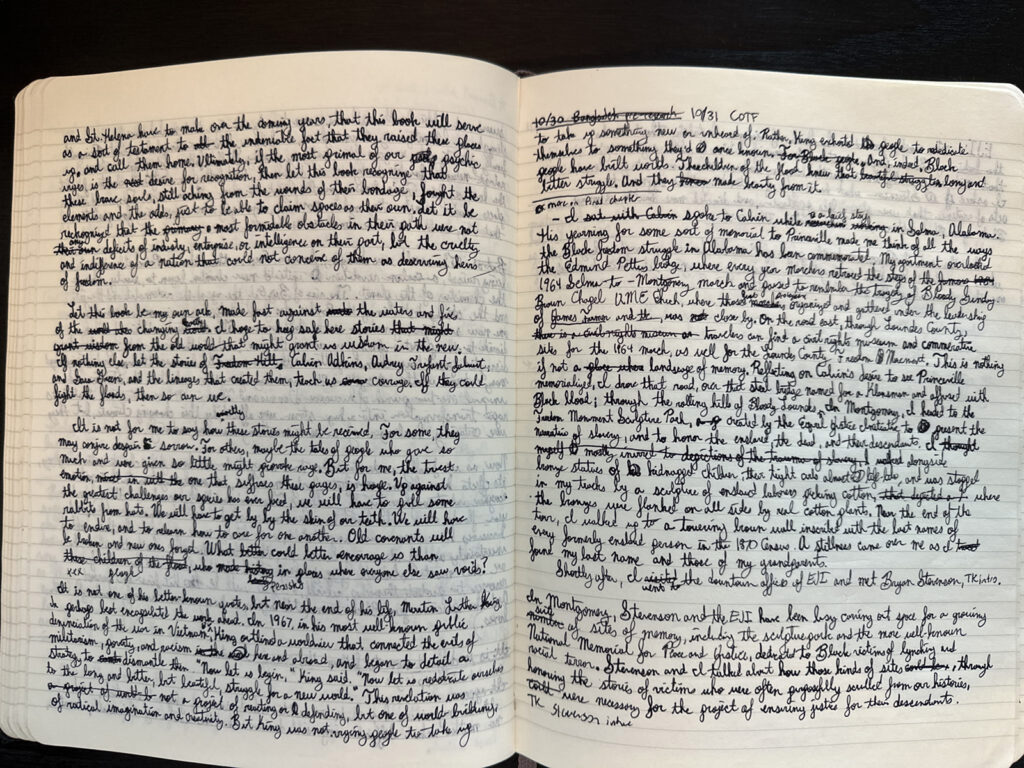

Vann is on a self-imposed two-week writing retreat, seeking silence and solitude to focus on a new project. In this quiet town, where only the song of cicadas can be heard over the rush of the river, Vann works in near-total isolation. There are no distractions—no television, nightlife, family, or friends, not even a movie theater within 30 miles—just the steady rhythm of his work, carrying him from dawn until nightfall.

At a makeshift desk in his rental apartment, Vann is immersed in the past to write his forthcoming book, Children of the Flood, which chronicles the histories of three of America’s earliest free Black towns: Princeville, North Carolina; St. Helena Island, South Carolina; and Ironton, Louisiana. These communities, established by formerly enslaved people in the aftermath of the Civil War, were shaped by Black resilience even as they weathered a century of white supremacist policies. Now they face new perils as climate change brings rising waters and flooding.

Much of the historical record in those towns has been washed away—by floodwaters or by neglect—but piece by piece, Vann is determined to tell their stories and offer a bridge between the past and the future. In Selma, he stitches together a patchwork history from the fragments that remain: century-old newspapers, photos, and town documents.

As told to New America, Vann shares the journey of writing Children of the Flood, the challenge of capturing lost histories, and the hope he finds in honoring his ancestors’ legacy.

I’m a big proponent of finding beauty in grief. The more intense the grief, the more intense the beauty.

That idea shaped Children of the Flood from the start. One of the first people I met for the book was Calvin Adkins, the town historian of Princeville, North Carolina. He believed Princeville’s history as the oldest town in America incorporated by Black people could literally help save it. In his estimation, if Americans understood its significance, maybe it could be protected, maybe it could be preserved. That belief felt especially urgent given that Princeville had already been devastated once before—by Hurricane Floyd in 1999. At the time I met Calvin, the community had spent nearly two decades rebuilding, buoyed by the hope that its story could be its shield. But six weeks after he and I met, Hurricane Matthew struck. The floodwaters came again, destroying homes, archives, and dreams. It was heartbreaking. At that juncture, I had met so many wonderful people who were rooting for Princeville’s future, and I knew this would feel like a death knell.

“To understand America, you must first understand a place like Mississippi.”

But the flip side is that people started reaching out. “We need the book out,” they said. “You’ve got to do this. It’s important to us.” That’s ecstasy. That’s why I keep going.

I’ve been reporting and writing this story since 2016, and honestly, it feels like everything I’ve done has led me to it. I didn’t set out to write about environmental disaster or climate change. What I wanted to write about was survival—and memory. How do communities make impossible choices between staying on the land their ancestors built, or leaving to survive?

That’s what these communities—Princeville, St. Helena Island, and Ironton—are grappling with. These are places built on the ashes of slavery and also, floodplains. This is land that no one else wanted. Now, when the waters rise, outsiders wonder, “Why do people stay?” When they should be wondering about the long history of redlining, disinvestment, and white supremacy. To me, that’s the center of the story.

A lot of what I call creativity is really just making connections between things. I think that’s partly my dyslexia—it’s made me see and organize the world differently. My brain is like the kitchen drawer where everything goes. There’s a kind of logic in there, even if it’s messy. I dip into that drawer constantly when I write.

My mom was the one who taught me to write. Having dyslexia meant becoming a journalist wasn’t the obvious path, but she never told me it wasn’t possible. She just said, “If this is something you want to do, then do it.” I’ve had great editors and mentors, but really, the only validation I ever cared about was hers.

Now I think about my work as a way of being a good ancestor. There’s this book by Olúfémi Táíwò, Reconsidering Reparations, where he talks about living intentionally as if you will one day be someone’s ancestor. That idea—that writing is a gift to people who will live after you—has shaped everything I do, especially this book. These towns have lost so much. And if I can help restore some of it, then it’s worth pursuing.

Vann’s eight-part podcast miniseries, “Floodlines,” covers Hurricane Katrina, a story of rumors, betrayal, and one of the most misunderstood events in American history.

I was born and raised in the South, and I think the South is where America is most honest about itself. There’s a quote from Faulkner that I come back to: “To understand America, you must first understand a place like Mississippi.” I really believe that. If you understand Mississippi, you understand everything else—our politics, our contradictions. When people express disdain for the South, I often think they’re expressing their discomfort with America.

But the South also holds the most aspirational parts of this country. These Black towns I’m writing about, and their citizens, are examples of that. Princeville was founded in 1865. The original name was Freedom Hill. It was literally built on the site where Union soldiers told Black folks they were free. A week earlier, those same people could have been flogged for trying to read. And yet, they built a town. If that doesn’t make you believe in human endeavor, I don’t know what will.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.