“I don’t report stories because I want to,” Caitlin Dickerson says. “I cover them because I feel like I have to.” That sense of duty—paired with relentless thoroughness and emotional clarity—has made her one of the most respected immigration reporters working today. A Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and staff writer at The Atlantic, Caitlin is known for telling some of the most complex and consequential stories of our time.

In 2023, she risked her life to report from the Darién Gap, a treacherous jungle passage between Colombia and Panama. “There’s no way to do it without risking your life,” she says plainly. She had watched the number of crossings through the region steadily increase, tracking the trend over time while traveling around the United States, Mexico, and Central America to interview migrants. But eventually, the story demanded more. “It brought together so many themes I’d covered, all in one place—failed policy efforts to curb migration, trafficking, cartel violence, climate change, the role of technology and social media, and the human toll of forced displacement.”

She didn’t take the decision to go lightly. “The list of people I would have been willing to go with to the Darién Gap was very, very short,” she says. When photojournalist Lynsey Addario texted her out of the blue, gauging her interest in a reporting trip to the area, Caitlin’s reaction was abrupt and resolute. She turned to her husband and said, “Shit, I’m going to the Darién Gap.” Lynsey and Caitlin had previously worked together in dangerous regions of northern Mexico. “Lynsey has a lot of experience in dangerous reporting environments. We’ve sat together and talked through what we do if we get kidnapped. I knew that I was going to feel as comfortable as one can in that environment going with her.”

“I don’t report stories because I want to. I cover them because I feel like I have to.”

But the story required more than courage. It demanded collaboration: with photographers, fellow reporters, fixers, and The Atlantic’s security team. “There’s this perception that journalism is a solo sport,” Caitlin says. “But that’s never been my experience. When Lynsey and I decided to go to the Darién Gap, the first people we called were other journalists who had experience on the ground there, and they were so generous with their advice.”

Caitlin’s devotion to journalism and storytelling was shaped by her childhood in Merced, an agricultural community in California’s Central Valley. “It looks more like Idaho than California,” she says, describing open fields, almond orchards, and dairy farms. The area was home to first-, second-, and third-generation immigrants, and everyone had to coexist. “I grew up with friends who were truly from all over the world,” she explains. Because the town was relatively small, it was impossible to exist in a bubble—she had no choice but to engage with a complex mix of cultural and political views, many of them unexpected. “Growing up in an area that was so diverse really drove me to seek out nuance in every story that I work on.”

That nuance became her trademark as a reporter. After an early, successful career at NPR, she joined The New York Times in 2016 and suggested immigration as a beat—not because she intended to specialize in it, but because she’d been drawn to it since studying under a historian of immigration at California State University Long Beach, which led her to become a voracious student of the subject. With that background of knowledge, she knew she could make an impact. “I had no long-term plan,” she admits. But when Trump won the presidency, immigration moved to the center of American political life. “For the next four years, my colleagues and I were all treading water, working seven days a week. I became nonexistent to friends and family.”

Over time, Caitlin developed greater fluency in the subject’s legal, historical, and humanitarian dimensions. “I reached a point where it would feel like a shame to move on to cover a different issue,” she says. “Immigration is one of those subjects that many reporters find really daunting. When you’ve invested years in learning the system, like I have, walking away from it feels crazy. It’s my job to stick with it.”

Her work isn’t without cost. Returning from difficult assignments often requires her to retreat socially, to recharge. “There are days where it feels like all I do is interview people about some of the worst experiences that a human being can have, like war, sexual assault and other forms of violence, exploitation that can result from living on the margins of society.” She leans on a close circle of friends and family who understand her rhythms. “I’m grateful that they are always willing to help me decompress if I need to talk about a story, but they don’t press for details unless I offer them because they sense how challenging the work is. Sometimes, I just want to eat a good meal and watch The White Lotus or something else that doesn’t require anything of me.”

Despite her growing list of accolades—the Murrow Award, a Peabody, a Pulitzer—Caitlin says she no longer seeks validation in trophies. “Honestly, at the beginning of my career, I think I did need that sense of validation because I was unsure of myself,” she explains. “I was surrounded by people from Ivy League schools, with family in the industry. I didn’t have that. Winning those early awards gave me a baseline feeling that I belonged.” Now, her satisfaction comes from the stories themselves: how deeply she can go, how much they move the reader.

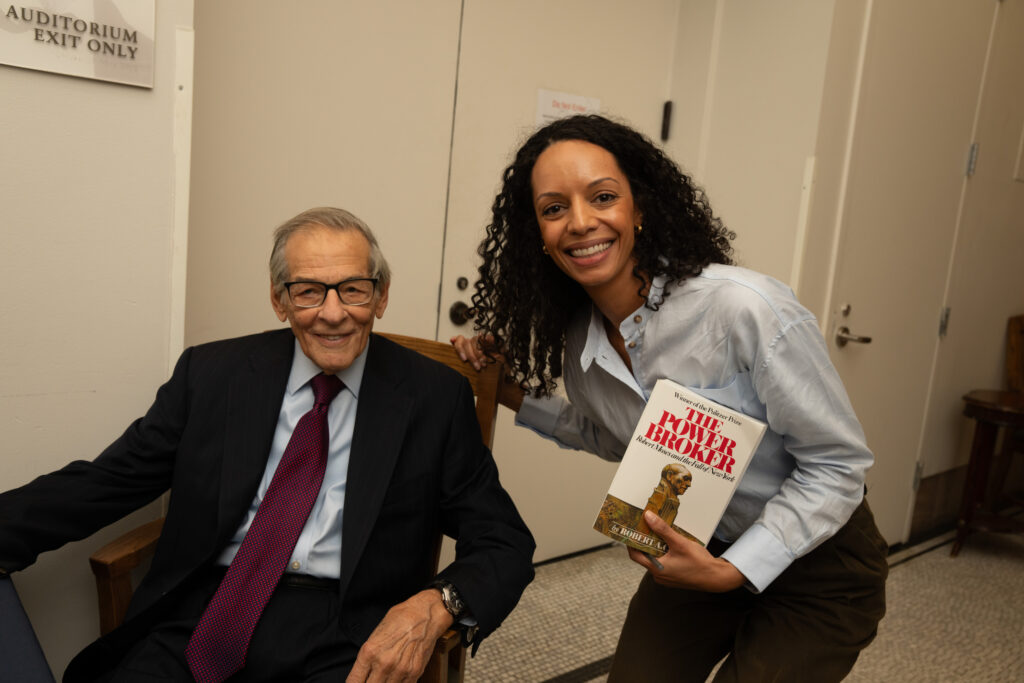

One of her heroes is Robert Caro, who once inscribed her copy of The Power Broker with the words: “For Caitlin—A fellow member of the craft.” It was a benediction. “He showed me what you can do if you take your time and turn every page,” she says.

That’s exactly what Caitlin Dickerson intends to keep doing.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.