This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Your book Language City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New York follows six New Yorkers all working to extend the lives of their languages. You are an accomplished linguist yourself, and yet, I think a lot of people would be surprised to learn that you were raised in a monolingual household. Can you talk about what drove your passion for learning and preserving languages?

That’s right, I grew up only speaking English—the language that my once multilingual family moved towards. My great-grandparents were Eastern European, Jewish immigrants who generally spoke four to five languages. And yet, English was all we spoke in my household. But I was surrounded by all of these other languages in other ways growing up—in the building where I lived, the streets that I walked, and the neighborhood I was raised in. A fascination and a curiosity about languages took root in me early on.

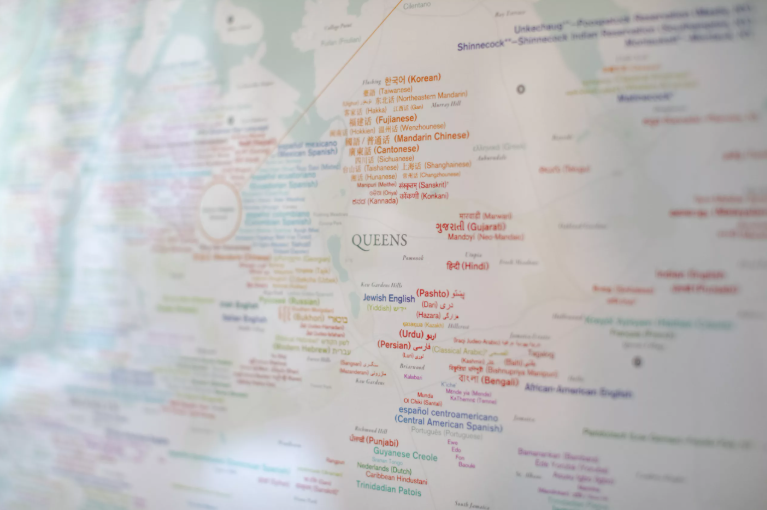

You live in, as you describe it, “one of [Queens’] quieter corners—a nondescript neighborhood with an extraordinary soundtrack.” What drew you there? And with your deep connection to language, can you imagine living anywhere else?

I do really love my neighborhood in Queens. It’s both this very ordinary place and also an extraordinary one. There are certainly very practical things that have kept me here for a decade—it’s still relatively inexpensive, it has public translation, it’s safe and liveable, and it’s actually positioned in the geographic center of New York, in terms of the five boroughs and the broader idea of the city. That means a lot to me, and is a big part of my work.

I go to all the boroughs and roam around the city widely, and it’s at the same time a place of languages from all over the world. It’s overwhelmingly immigrant, and that includes speakers of dozens of different languages, from Latin America, Central and Eastern Europe, and different parts of Asia. So, what I love about it is its “ordinary extraordinariness.” It’s hard to imagine living anywhere else. But at the same time, nothing is perfect. Nothing lasts. I want to be part of the changes in the best possible way.

In Language City, you write that “the subway might not run throughout the world, but it can contain and display it, at all hours, for anyone who cares to see.” What does riding the subway reveal to you about the richness of human life and language in New York City?

The subway is the great public space of New York City. It’s a mobile one and an ever-changing one. It highlights the intensely practical, political, and daily nature of diverse life in urban spaces. The subway certainly has its problems, but it dwarfs all the other public transit systems throughout the United States by a huge margin. It is the lifeblood or the circulatory system of the city, and it is a deeply democratic space. It’s the polar opposite of climbing into an Uber where you are paying a distant company that is trying to automate all labor out of existence. In riding the subway, for better or worse, you have to encounter other people; you have to encounter differences. You have to work it out.

I’ve seen the MTA [Metro Transit Authority] post notices in languages that are otherwise almost never seen publicly in the U.S., certainly not from government agencies. At the Elmhurst Avenue station in Queens, I spotted a ‘“change of service”’ MTA notice posted in Burmese and Indonesian. That’s extraordinary.

Do you find yourself overhearing a rarely spoken language and stopping to ask someone what it is they’re speaking?

Sometimes I can’t help myself. It is my lens on the city—to listen in on the languages. It is my way of living in the world. There’s a lot of things one can notice without intruding on anyone’s privacy.

I saw a car parked the other day with a vanity license plate that said: “SYLHETI.” This is a language and an identity from Northern Bangladesh. There are a lot of Bangladeshi New Yorkers who speak Sylheti. Here was somebody proud [enough] to get the vanity license plate.

Language City includes a striking quote from Ludwig Wittgenstein: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” How do you interpret that idea in your work as a linguist?

I think it points to a kind of fundamental humility that we all need to have. There are 7,000+ languages in the world. We need to realize that the languages we grew up with and the ones we know best shape our way of seeing the world in very fundamental ways. We need to have a deep humility in the face of other languages.

The pandemic made clear that language access can be a matter of life and death. What did you witness while living in NYC at the height of COVID-19, especially around efforts to translate and disseminate health information?

When New York City became the epicenter of COVID in March 2020, the epicenter of the epicenter was in the middle of the most linguistically diverse neighborhoods in Queens. As a resident of the area, watching the crisis unfold in real time, I observed a number of factors at work. Multilingual immigrants were more likely to be essential workers, whether in hospitals or restaurants. One major issue was overcrowded housing. But also, information was not available in people’s languages in a timely fashion, when a few days could make a major difference. The tragically higher incidences of COVID were substantiated by comparing our New York City language map with the case data from the NYC Department of Health.

There were lessons for preparedness for a linguistic emergency and having the language access measures and personnel in place to be able to respond.

On the positive side, it fell to communities and individuals to record PSAs and spread the word through WhatsApp, WeChat, and informal networks, to give people information on how to protect themselves. My organization, the Endangered Language Alliance, ran a series of events in more than a dozen different languages on the vaccine. These were languages that nobody was really spreading the word in.

It’s not really clear to me whether lessons have been learned or if language access has improved in those places. The magnitude of the challenge and the lack of really any language policy apparatus are still glaring.

In a footnote in your book, you mention that the Jehovah’s Witnesses website—available in over 1,000 languages—is the most multilingual website in the world. How did that come to be, and what do you think it reflects about the role of translation?

I am starting to work on a new project connecting language and religion and the fundamental role that Bible translation and evangelism have played in the documentation of languages, research on linguistic diversity, literacy, and publishing. The connection is particularly strong for vast evangelical movements.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses’ extraordinary website is a striking example of that and a testament to their seriousness, at least in putting out a welcome mat for many of the most marginalized people in the world who speak this huge range of indigenous languages.

On March 1, President Trump signed an executive order making English the sole official language of the United States. In response, you and colleagues at the Endangered Language Alliance asked pointedly: “Despite the United States’ rocky relationship with diversity, no administration felt obliged to impose an official language for 250 years. Why now?” What concerns you most about the broader implications of this order?

This is a major step backwards, in part because it repeals one of the very few pieces of language access legislation that existed at the federal level, which required federal agencies to make language access plans.

The executive order flies in the face of everything America has been culturally and linguistically for its entire history. There’s a reason why there’s never been an official government-mandated language imposed upon a fundamentally multilingual place, which is not only anchored in hundreds of Native American languages—many of which are fighting for their lives against incredible odds—but also a land of many hundreds of immigrant languages that are woven into the fabric of the country.

What did you gain from your fellowship with New America?

The sheer variety of ideas and methodologies that I was able to encounter—from people with medical and journalistic training to public health expertise to documentarians. I was able to get a brief, but powerful glimpse into their creative and professional processes that opened up those fields to me in a way that I could then see drawing on in the future.

It was a powerful experience and an extraordinary group of people.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.