This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You’ve shared how an experience of near heat exhaustion in Phoenix—running 15 blocks in summer—became the catalyst for your book The Heat Will Kill You First. This led to your realization that we should view heat as “an active force.” Why do you think so many of us don’t truly understand the risks of extreme heat?

Because heat, unlike other forms of extreme weather, is invisible. Looking out the window in my office in Austin right now, I can’t tell if it’s 70 degrees outside or 120 degrees. If there is a hurricane, on the other hand, I know it: The wind howls, the trees shake. So, there are no visual cues for heat, nothing that imprints it in our imagination.

Also, the media is very bad at communicating about the risks of heat. When weathercasters talk about heat waves, they often accompany it with images of people at the beach or playing in sprinklers. There is very little attempt to talk about risks or dangers.

Finally, the simple fact is most people prefer warm days to cold days. We prefer flip-flops to snow boots. And so we have a very hard time understanding how quickly the comforts of warm weather can tip into the dangers of extreme heat.

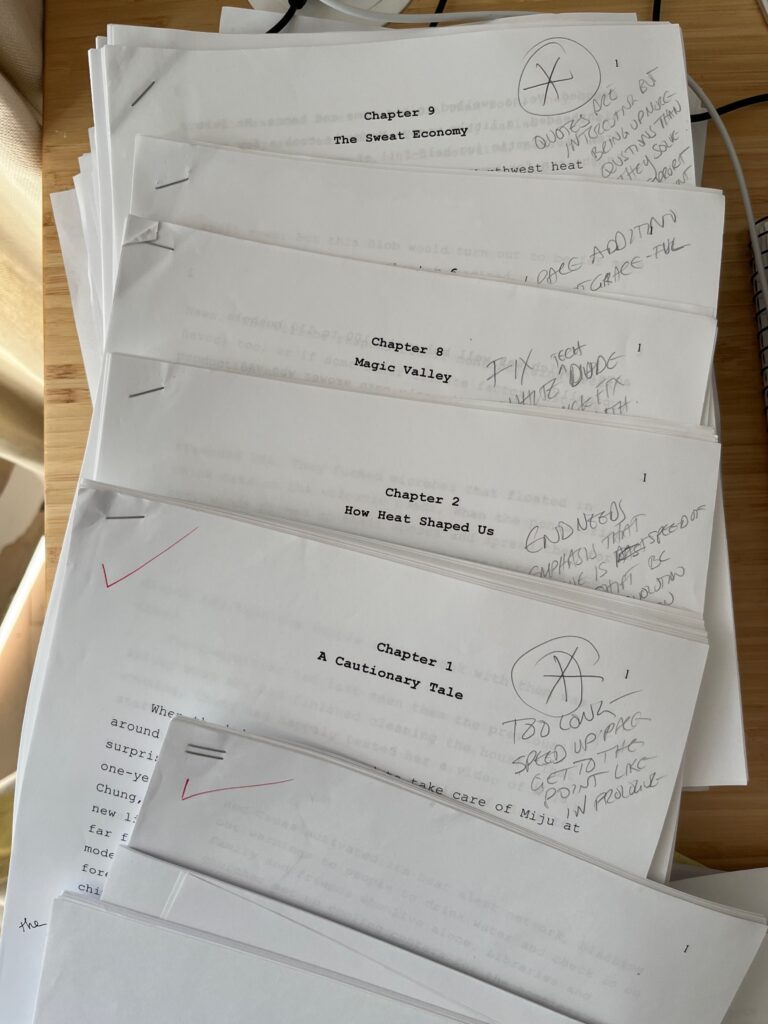

In an interview with The Story, you explained that the problem with most climate writing is essentially one of intention. “Most people who write about climate don’t think about it as a story,” you said. “They think about it as information.” Can you elaborate on how you turn facts into stories to draw in readers?

Well, I don’t think what I do is actually turn facts into stories. I think I use facts to build the world that the stories I write exist in. To write about the dangers of extreme heat, for example, I read a lot of science papers that looked at the human body’s tolerance for heat, and I learned as much as I could about the mechanism by which heat damages cellular structures, etc. The more I learned, the better I understood how it all worked. But to turn that into a chapter of a book—at least the kind of book I wanted to write—I had to find a narrative that would carry all that.

Around that time, I happened to read about a family that had gone out for a hike on a summer day in the Sierra Nevada foothills and didn’t return home. When a search party went out to look for them the next day, they were found dead on the trail. It took more than a month for investigators to determine that the cause of death had been heat stroke. I decided to build the opening chapter of the book around that family’s experience, which allowed me to build a narrative with some human drama, while at the same time sneaking in a lot of science about how heat impacts the human body. To me, the story is a vehicle for the science. But I try to keep that a secret from my readers.

When you know as much dire information about our warming climate as you do, and you’ve been reporting and telling stories for as long as you have, how do you continue to find optimism and hope?

There are lots of different ways to think about hope and optimism. There is cheap hope and hard-won hope. There is optimism that is rooted in ignorance of the scale of the challenges we face, and optimism that comes out of a deep trust in human ingenuity and imagination. Myself, I am just constantly inspired by the people I meet—scientists, activists, entrepreneurs, artists, community leaders—who are fighting hard to build a better world. That might sound corny, but it’s true.

What do you think of the phrase “human resilience” when it comes to Americans living in some of the hottest places in the U.S.?

I don’t know what the phrase “human resilience” means. Humans are obviously incredibly resilient creatures—as a species, we are like cockroaches, almost impossible to kill. What’s fragile is our way of life and, in the long run, civilization itself.

Do you think certain places in America should be deemed “uninhabitable” because of warming temperatures?

Uninhabitable? No. With enough technology and supplies, humans can live on the moon. But why would you want to? The same is true with hot cities like Phoenix and Houston and Austin. As the heat rises, life will change. Outdoor work will become impossible in the summer, as will outdoor concerts and sporting events (goodbye, summer high school football-training camps). Loss of air-conditioning during power failures will not just be an inconvenience but a potentially deadly event. Steel bridges will crack in the heat. More and more people will lead vampire lives—indoors during daylight, outdoors at night. Some people will decide to try to live with it. But a lot of others will flee to cooler, more hospitable climates. In that sense, climate-driven extreme heat poses a real threat to the economic and cultural vibrancy of hot cities like Austin and Phoenix and much of the southwest. And the hotter it gets, the bigger the impacts will become. To imagine that we are just going to air-condition our way out of this is profoundly naive.

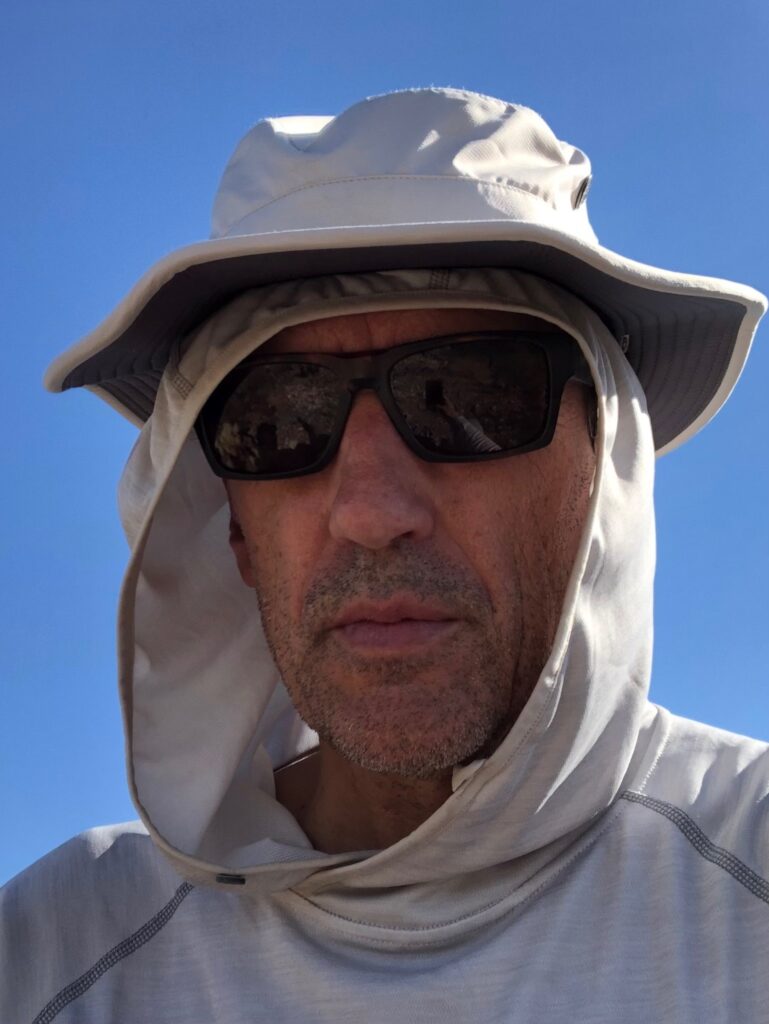

You moved from upstate New York to Austin, Texas, and now live in a state that regularly experiences 100+ degree temperatures. How have you adapted to the heat?

I try to get out of Austin as much as I can during the summer. I go for walks and hikes early in the day. I have made peace with our air-conditioner (which is powered, I should add, by a heat pump, a terrific heating/cooling device that allowed us to get rid of our gas-fired AC unit).

I go for frequent swims at Barton Springs, Austin’s wonderful spring-fed public swimming pool. I don’t know how long I’ll stay in Austin, but for now, my wife has a good job here and two of my kids live here and the tacos are great, so I’m going to stick around for a while. And for me, there is some virtue in living in the story you are writing about. Texas is the belly of the beast—besides heat, we have droughts, wildfires, sea level rise, hurricanes, invasive species, crop failures. It’s a Disneyland of climate impacts.

You’ve said that the New America Fellows Program gave you the “intellectual camaraderie” you needed “to write the book I wanted to write.” Could you elaborate on those relationships and their impact?

Writing a book—especially a nonfiction book tied to current events—is a solitary trip through the wilderness. As one writer I know put it, “There are no ways of doing it. There are only ways it’s been done.” At New America, I gained a lot by being in conversation with other writers and hearing how they had done it or were doing it.

During one meeting at New America, I remember talking to Chris Leonard about his book about the Koch empire and the difficulty of writing a book about people who don’t want you to write it. And Peter Bergen, about the challenges of covering the Iraq War. And Mattieu Aikins, who was just finishing up his book about Afghan migrants. And Lisa Hamilton, who was working on her book about an immigrant rice farmer in California’s Central Valley. Being with other writers who are on the same journey—even if the landscape they are traveling through is very different—was tremendously inspiring.

None of the conversations we had were profound. They were more mechanical, about research tips and agent woes. And, of course, writerly whining and moaning: You hate writing footnotes too! Your editor hated your first draft too! You are struggling to come up with a title too! All in all, New America gave me the feeling that I was not in this alone, that the work I was doing was important, and that it could, if I did my job well, make a difference in the world.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.