This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You’ve described yourself as being endlessly curious about how things work (or don’t work). So much of your recent writing has been focused on the housing crisis. What about this topic is most interesting to explore?

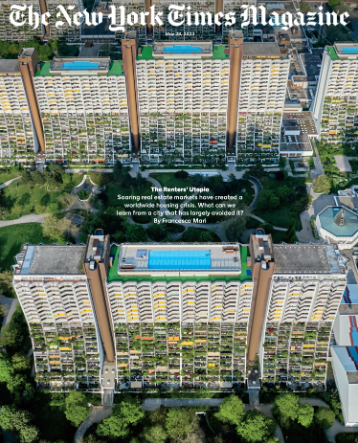

Shelter is a basic human need, a need that’s been addressed with endless ingenuity and art. So many fascinating factors are involved: design, materials, building code, land use policy, housing finance, law, and cultural ideas around what good living looks like. And yet we’ve allowed housing to become an investment vehicle and an increasingly speculative asset. I try to understand how that happened and why it doesn’t need to be that way. Everyone deserves a safe, beautiful, affordable place to live.

You are a born and raised Californian, but you went away for college and didn’t return until your 30s. You’ve said you were shocked by the inequality you discovered in the “new San Francisco.” What were some of the things that you saw on your return that stuck out most to you?

Working families sleeping in their cars. Blocks-long homeless encampments. A needle jammed into the broken light fixture outside my apartment door. Within two months, my car was broken into three times, the windows smashed into tiny cubes of shatter-proof glass. In the first break-in I lost a backpack with notebooks of value only to myself. The next two times, I was wiser and there was nothing to steal. With the median housing cost over a million dollars, I imagined that the city had become one big rage room.

In the waiting room of the car window repair shop where I’d become a familiar face, I met a twenty-something who worked for Airbnb. He was also getting his window repaired. He invited me to dinner at the company cafeteria—I counted something like 21 local brews on tap—where he evangelized about cryptocurrency. He invested all his savings in bitcoin, which was running at about five or six thousand per coin at the time. He’s likely now a multimillionaire.

Money starts to seem senseless in the Bay Area, divorced from labor and actual productivity. How can a place ostensibly so committed to equality achieve so little of it? Nowhere is this more evident than in housing. In San Francisco, it costs $1 million to build a single unit of affordable housing. No one benefits from that, because it stokes inequality, and understandable rage.

In your article “How an American Dream of Housing Became a Reality in Sweden,” you detail how Sweden has been able to address the housing crisis through an investment in industrialized, modular housing. I was struck in particular by one of your data points—women make up less than 15 percent of U.S. construction workers. At the Swedish construction company Lindbacks, more than 30 percent of the workforce is female. What would it mean for the industry if more women were involved in construction?

Any industry benefits from the labor and insight of a gender that makes up half the population. Lindbacks said it attracted a greater variety of workers, including women, because building in a factory environment means regular hours, a controlled environment, safe working conditions, and predictable outcomes and timelines. It makes sense that more women would be drawn to assembling a beautiful, pragmatic product.

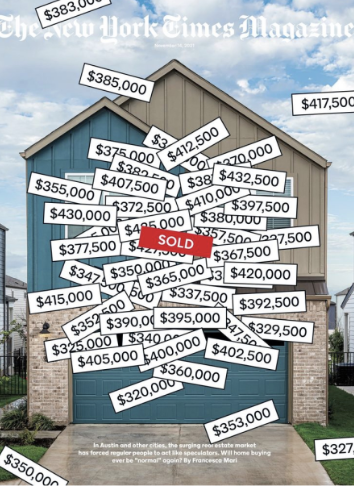

You lived for several years in Austin, Texas, writing for Texas Monthly. In 2023, it was reported that Texas built more homes than any other state in the country. In fact, it built 300 percent more homes than your home state of California. Having lived in both places, what lessons have you drawn from how Texas has approached housing, accessibility to land, and regulation?

According to a recent RAND study, it’s more than twice as expensive to build multifamily housing in California than in Texas. Municipal impact and development fees average $29,000 per unit in California, compared to less than $1,000 per unit on average in Texas. Projects in California take an average of 22 months longer. There’s no question that California’s excessive regulation around building has backfired. Californians are now flooding Texas, attracted by the lower cost of living.

But while I think there’s much to admire about having less restrictive building codes and fewer zoning restrictions, a fair amount of the building in Texas is sprawl. (And a city like Austin was the site of some of the highest property inflation during the pandemic.) I’m more inclined to look to social housing in a flourishing metropolis like Vienna, for solutions. Social housing is insulated from the market, either run by limited profit housing associations that charge “cost rent” (a particularly precise Viennese term for rent priced according to the cost of operating the property including a modest profit capped between roughly 3 to 5 percent, rather than priced according to what the market will bear) or municipal authorities charging a fixed rent.

In an interview with The New York Review of Books, you explained, “I’m always pre-reporting four or five stories at a time.” How do you know when one of those stories is “the one” worth doubling down on and turning into a project?

Pre-reporting can be as simple as slipping a conversation with an acquaintance into a mental drawer for later consideration or it can be diving into documents and making dozens of phone calls. I generally come to stories in one of two ways: top down, in which I identify a theme I want to explore and then look for a narrative that will help me unpack the issues, or bottom up, in which I come across a compelling story that feels like it speaks to larger issues. As for when to go all in, I trust my gut… and it’s right 75 percent of the time. But every year, I spend at least a couple months on something that doesn’t pan out or that someone else nails before me. I think it’s the unfortunate cost of doing original work.

How has being a freelance writer and an editor influenced how you teach narrative nonfiction to college students?

I teach the class I wish I had been able to take as an undergraduate. I don’t much believe in writer’s block; I believe in reporter’s block. But reporting can be taught. Read, live, listen, observe: There are infinite ideas out there. I try to help my students recognize and catch them. We have weekly editorial meetings to discuss pitches and to figure out which are worth pursuing, how they might be strengthened, and the best way to execute them. Perhaps what I’ve learned as an editor and freelancer is when to hold on to an idea and when to let go. Not every idea is a good one.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.