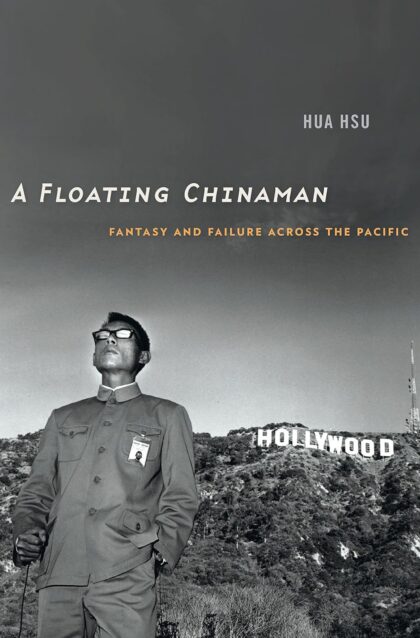

Who gets to speak for China? During the interwar years, when American condescension toward “barbarous” China yielded to a fascination with all things Chinese, a circle of writers sparked an unprecedented public conversation about American–Chinese relations. Hua Hsu tells the story of how they became ensnared in bitter rivalries over which one could claim the title of America’s leading China expert.

The rapturous reception that greeted The Good Earth—Pearl Buck’s novel about a Chinese peasant family—spawned a literary market for sympathetic writings about China. Stories of enterprising Americans making their way in a land with “four hundred million customers,” as Carl Crow said, found an eager audience as well. But on the margins—in Chinatowns, on Ellis Island, and inside FBI surveillance memos—a different conversation about the possibilities of a shared future was taking place.

A Floating Chinaman takes its title from a lost manuscript by H. T. Tsiang, an eccentric Chinese immigrant writer who self-published a series of visionary novels during this time. Tsiang discovered the American literary market to be far less accommodating to his more skeptical view of U.S.–China relations. His “floating Chinaman,” unmoored and in-between, imagines a critical vantage point from which to understand the new ideas of China circulating between the world wars—and today, as well.