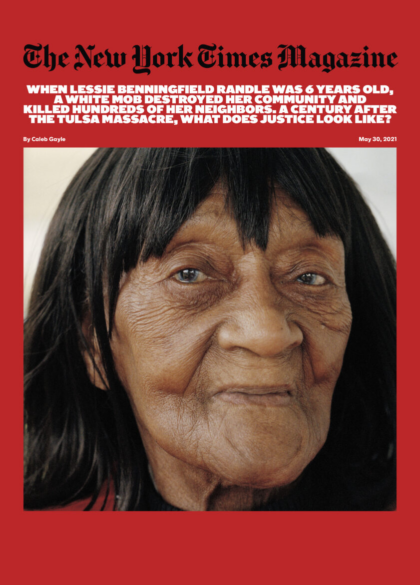

Caleb J. Gayle wrote a cover story for the New York Times Magazine about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and the search for justice 100 years later.

Tulsa, and Oklahoma more generally, was becoming a destination for Black people who wanted a better life. All over the state around the turn of the 20th century, Black townships were springing up — more than 50 of them by 1920. An article in The Muskogee Comet, a Black newspaper, from June 23, 1904, proclaimed that the Tulsa area “may verily be called the Eden of the West for the colored people.”

The money a Black resident like Rebecca Brown Crutcher spent and earned from her barbecue pit would cycle through her community a dozen times before a white hand would touch it, according to Ellsworth. Black Tulsans, he writes, could buy “clothes at Black-owned stores, drop off their dry cleaning and laundry at Black-owned cleaners and have their portraits taken in a Black-owned photography studio.”

But if Eden was Black Tulsans simply going about life on their own terms, it was not free of evil. Senate Bill 1, the first law passed by the new State of Oklahoma in 1907, was a Jim Crow act that segregated Black Oklahomans from everybody else. It prohibited Black and white passengers from occupying the same railroad cars — and then was extended to ban the sharing of public and private spaces throughout the entire state. The deep division between Black and white Tulsa, the very reason for the high concentration of Black people in Greenwood, was in part a response to these governmental measures. But it took extralegal violence to crush the rise of enterprising Black Tulsans.