Theodore R. Johnson wrote about how the black vote became a monolith and the role of racial equality for the New York Times Magazine.

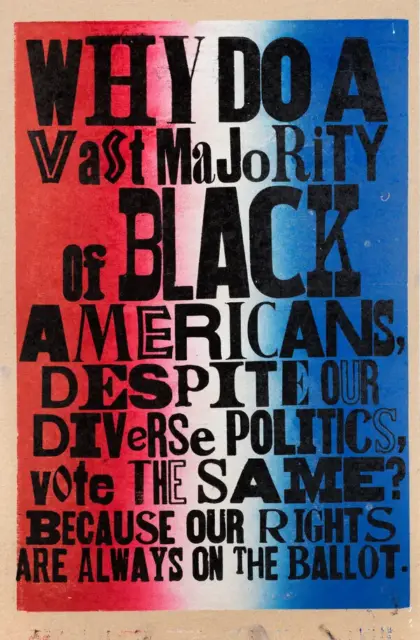

An enduring unity at the ballot box is not confirmation that Black voters hold the same views on every contested issue, but rather that they hold the same view on the one most consequential issue: racial equality. The existence of the Black electoral monolith is evidence of a critical defect not in Black America, but in the American practice of democracy. That defect is the space our two-party system makes for racial intolerance and the appetite our electoral politics has for the exploitation of racial polarization — to which the electoral solidarity of Black voters is an immune response.

It is, however, routinely misdiagnosed. In 2016, campaigning in a Michigan suburb that is around 2 percent Black, Donald Trump prodded Black voters to give him a chance, asking: “What the hell do you have to lose?” and boasted to the nearly all-white audience: “At the end of four years, I guarantee you that I will get over 95 percent of the African-American vote. I promise you.” Earlier this year, the Democratic presidential nominee, Joe Biden, stated matter-of-factly that “unlike the African-American community, with notable exceptions, the Latino community is an incredibly diverse community with incredibly different attitudes about different things.” More crudely, he told the radio host Charlamagne Tha God in May: “If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t Black.” (He later distanced himself from both comments.)

These characterizations belie a more ominous reality: Black Americans are canaries in the democratic coal mine — the first to detect when the air is foul, signaling the danger that lies ahead.