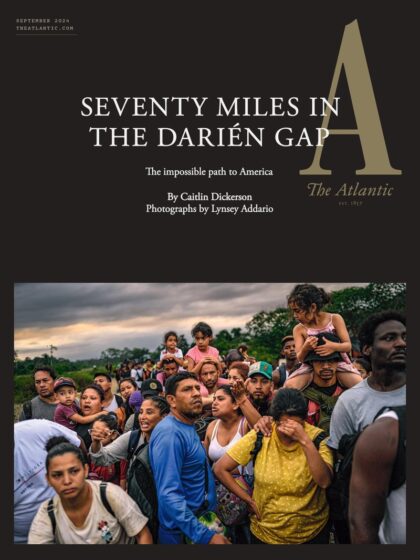

Caitlin Dickerson wrote a cover story for The Atlantic about migrants risking treacherous terrain, violence, hunger, and disease to travel through the jungle to the United States.

They gathered in the predawn dark. Bleary-eyed children squirmed. Adults lugging babies and backpacks stood at attention as someone working under the command of Colombia’s most powerful drug cartel, the Gulf Clan, shouted instructions into a megaphone, temporarily drowning out the cacophony of the jungle’s birds and insects: Make sure everyone has enough to eat and drink, especially the children. Blue or green fabric tied to trees means keep walking. Red means you’re going the wrong way and should turn around.

Next came prayers for the group’s safety and survival: “Lord, take care of every step that we take.” When the sun peeked above the horizon, they were off.

More than 600 people were in the crowd that plunged into the jungle that morning, beginning a roughly 70-mile journey from northern Colombia into southern Panama. That made it a slow day by local standards. They came from Haiti, Ethiopia, India, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Venezuela, headed north across the only strip of land that connects South America to Central America.

The Darién Gap was thought for centuries to be all but impassable. Explorers and would-be colonizers who entered tended to die of hunger or thirst, be attacked by animals, drown in fast-rising rivers, or simply get lost and never emerge. Those dangers remain, but in recent years the jungle has become a superhighway for people hoping to reach the United States. According to the United Nations, more than 800,000 may cross the Darién Gap this year—a more than 50 percent increase over last year’s previously unimaginable number. Children under 5 are the fastest-growing group.