Perhaps one of the most neglected groups in America is the working homeless—people who hold down jobs yet remain unhoused, caught in the brutal gap between wages and rent. As a trained anthropologist turned journalist, Brian Goldstone has spent years documenting the lives of those enduring in the shadow lands of the U.S. economy. His debut book, There Is No Place For Us: Working and Homeless in America, developed during his New America fellowship, unflinchingly chronicles this crisis of contemporary American inequality.

Drawing on immersive fieldwork and narrative depth, Brian renders the stories of the working homeless not as abstract social commentary but as irreducible, deeply human portraits—refusing the familiar tropes of blame or redemption. In doing so, he challenges one of the most persistent myths in American life: that housing insecurity is a personal failure, rather than a policy choice. “When someone loses their home,” he said, “it should be seen as a profound injustice—but it’s not. It’s made into a personal failure.”

That impulse to question dominant narratives stems, in part, from a lifelong tendency to swim against the tide—whatever the setting. “I wouldn’t trade my various crises of unbelonging for anything,” Brian told me. “If nothing else, it gave me an inclination to explore not just people and places, but ideas that were outside of the norm. I embraced questioning the moral, social, and political status quo.”

We spoke with Brian about the making of the book, the uses of anthropology beyond the academy, and how never fully belonging has made him a better writer.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You’ve said you never felt like you fully belonged—to your faith, your school, even your discipline. How has that outsider status shaped the way you move through the world?

It’s funny, but in hindsight, I’ve almost come to think of it as a kind of superpower. Growing up, I was always in this in-between space—ethnically Jewish, raised in a Pentecostal church; a punk-loving kid obsessed with poetry and literature at a conservative Christian school. I was always struggling to fit in, often isolated, partly because I never felt at ease within any given category or identity. It was painful at the time. But it planted the seed for how I understand the world. I’m interested in life at the margins, in difference, in what lies under the radar. And I gradually realized that not fitting in—socially, culturally, intellectually—allowed me to notice things that others might overlook.

How did that sensibility lead you to write about homelessness, especially in There Is No Place for Us?

It actually started in high school. I was a terrible student and got into a lot of trouble. After one of my many infractions, my parents made me volunteer at a homeless outreach center in Atlanta. That was my first real encounter with people who were unhoused—and their stories were so complex. They had aspirations, passions, flaws, and regrets. They weren’t these caricatures that society tries to make them into. Over time, I kept returning to this question: Why is homelessness treated as inevitable in America? How has this become a normal feature of urban life in the richest country on Earth?

Your book focuses on the working homeless—people with jobs who still can’t afford a place to live. Why did you choose to center those stories?

Because their stories explode the myth that homelessness is about individual failure.

When my wife, who’s a nurse practitioner, started telling me about patients who were employed but living in shelters, I was floored. These include daycare workers and home health aides. They were doing essential jobs—caring for our kids, our elders—and still couldn’t afford rent. I typed “working homeless” into an academic database and found almost nothing. That silence told me something. These people’s lives weren’t being taken seriously, even in research.

You left academia to pursue longform journalism. Was that another act of unbelonging—or liberation?

Both. I had done the PhD, the postdoc, the whole academic track. But I felt like I was swimming against the tide of what an anthropologist was supposed to be. I wanted to experiment with form, to foreground storytelling, to move beyond the university. When Harper’s accepted my first pitch, it was a turning point. I realized I could follow my curiosity wherever it led me—stories on opioids in Montana, or asylum seekers in Israel, or psychiatric healing in Ghana.

I’m still not sure what to call myself. Am I a writer? An anthropologist? I think I just follow what’s urgent and try to make meaning of it.

You’ve described your own neighborhood in Atlanta as a progressive enclave, and yet you’ve witnessed opposition to low-cost housing out of a concern for “the character of the neighborhood” and possible damage to attractive tree canopies. What do you make of those conflicting stances?

What I’ve observed in my own neighborhood in Atlanta is representative of the housing debate going on in any other city across the country. There’s a refusal in neighborhoods to allow those who are in most desperate need to live in their communities. When the subject of affordable housing comes up, well-meaning liberal homeowners will—for example—complain about things like the possibility of increased traffic, and that’s really just a cover for their desire to keep property values as high as possible. It’s fighting an uphill battle against people who wield a lot of power.

These are the dynamics and trends that I’m documenting in Atlanta, where what was once known as the “inner city” is now revitalized with luxury condos. The remaking of urban space is coming at the expense of the very people whose labor has made that growth possible. That’s a perverse reality that’s found across the country.

What gives you hope—especially in the face of a crisis as entrenched and overwhelming as housing insecurity?

The fact that there’s a growing tenants’ rights movement, even in the face of enormous odds. The public discourse around housing insecurity has tried to trap homelessness in a binary—either compassion or judgment—but what’s been left out for too long is justice. The people I met while reporting this book—people living in cars, working multiple jobs, raising kids—have every reason to feel exhausted. And yet, some of them are still standing up and demanding change. That, to me, is inspiring.

July 9, 2025

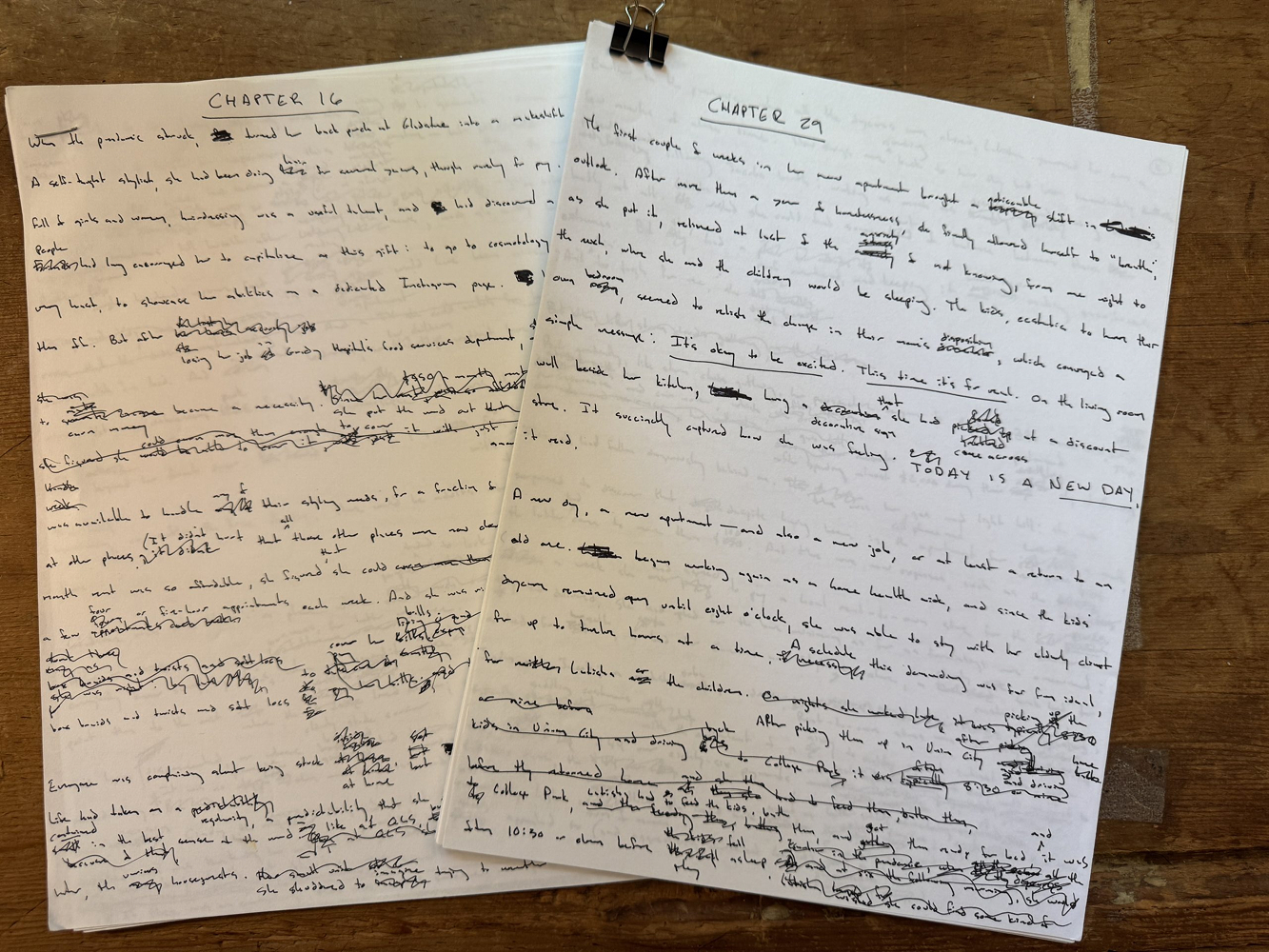

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.