This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Your film, Sugarcane, tells the story of an investigation into abuse and missing children at an Indian residential school. How did you come to make this film?

In the spring of 2021, when news broke about the discovery of unmarked graves at a former Indian residential school, I had this gut [reaction]. I reached out to my old colleague Julian Brave NoiseCat right away. Julian is a tremendous writer, historian, and storyteller. We worked our first reporting jobs together and had been trying to find a project to collaborate on ever since.

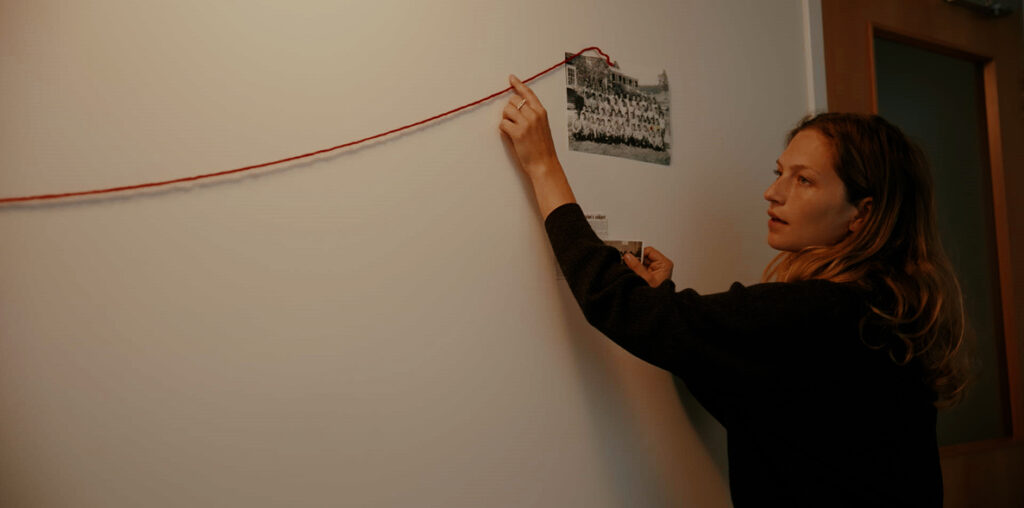

Then, I went looking for a First Nation individual who had announced they were beginning their own search, and I found an article in The Williams Lake Tribune about Chief Willie Sellars. I reached out. He called me back that same day. “The Creator has always had good timing for me,” he said. “Just yesterday our Council said we need someone to document our search.” Two weeks later, when Julian called again, I told him I was planning on following the search at St. Joseph’s Mission near Williams Lake. He paused. “That’s the school where my family was sent and where my father was born…” Out of 139 schools, I chose the one where Julian’s origin story began.

While you have covered stories across the globe, this project brings you back to your home country of Canada. How was your experience as a journalist and filmmaker different in a more familiar place?

Sugarcane marks the first time I’ve turned my lens on my own country, its original sin, and the horrors it perpetrated against First Peoples. I felt a more direct responsibility to help uncover the truth and ensure that Canadians understood this foundational atrocity on which the country was built. The last residential school closed during my first year of kindergarten, and yet, I didn’t know these schools existed until I became a journalist.

In a previous interview with New America, you described once seeing Canada as a gentler, kinder version of America. But in tracing the history and legacy of Indian residential schools, you’ve had to confront a much harsher truth. What has that journey taught you about questioning the histories we’re taught—and how we come to accept them as final?

Most histories included in our grade school and high school curricula have glaring omissions. They tell a story from a perspective that we’re meant to accept as absolute and as a final ruling on truth. Once you realize how many voices and experiences are missing from that narrative, the grounds and framework of your understanding of the world start to shake. Who gets to tell the story of what happened and what they might choose to highlight or ignore can tell us as much about the dynamics and power structures of the time as the history itself. I think documentary film and journalism at their best help us subvert the status quo and illuminate new ways of thinking and seeing.

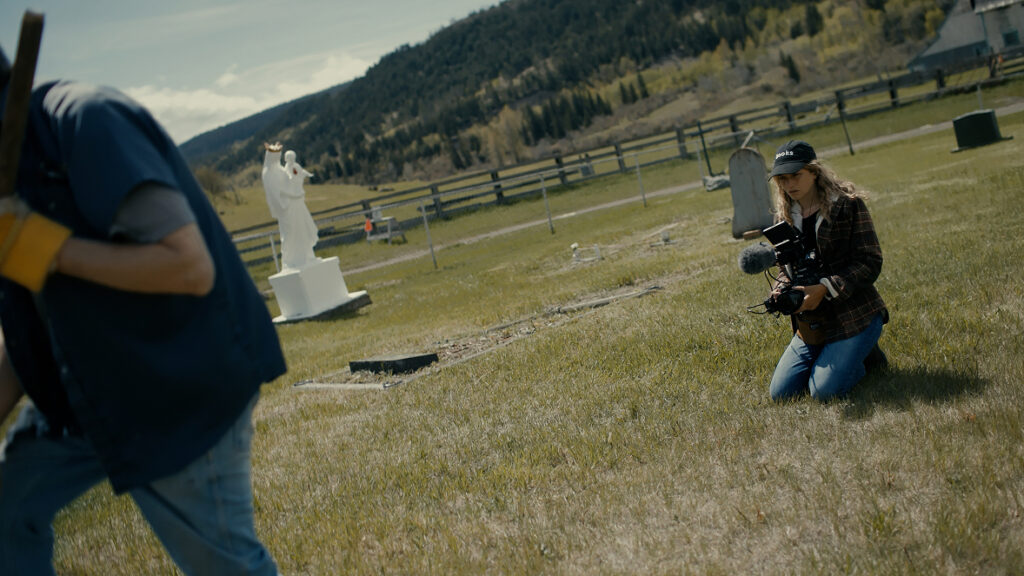

Sugarcane uses a documentary style known as cinéma vérité, which emphasizes realism and close observation. Can you describe what that approach entails—and why it felt essential for telling this particular story?

We felt that to tell this particular story, we had to live it, and bring the audience into the urgent and present consequences of the residential schools and all that they wrought. We also felt that the film needed to reject the historically colonial approaches to telling native stories from an anthropological and arms-length perspective. So we eschewed formal interviews and more standard conventions to get under the skin of what it was like to live this moment through the lives of our participants. That required building real trust over many years, participating and living in reciprocity with the community in Sugarcane.

We also shot the majority of the film on prime lenses, meaning that we couldn’t zoom in. So in order to get close, which much of the film is, we had to really gain that intimacy, and you can feel it through the lens. We also believe this is an epic world worthy of epic cinema and storytelling, and vérité filmmaking can lend itself to feeling more like fiction, with real tension and scenes and story arcs.

You’ve said one of your hopes for Sugarcane is that it becomes part of school curricula in Canada. What kind of impact do you think it could have on future generations—especially those who would be learning truths you never encountered in school?

We have been working to get Sugarcane into schools and universities across Canada and are working with Canadian Geographic to build specific curricula around it. I hope that the inclusion of the film helps generate dialogue and pushes students to question the structures of power and narrative that they are handed, and more specifically, how to think critically about the way Indigenous communities are struggling and rebuilding in the wake of historical wrongs. Fundamentally, I hope and believe the film has shifted the understanding of what these schools really were and how they brutalized communities. We’ve been so thrilled to see the Canadian government embrace the film—they’ve been showing it to Parliament, policymakers, government workers, and across embassies worldwide, so the narrative shift is happening at every level.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.