This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

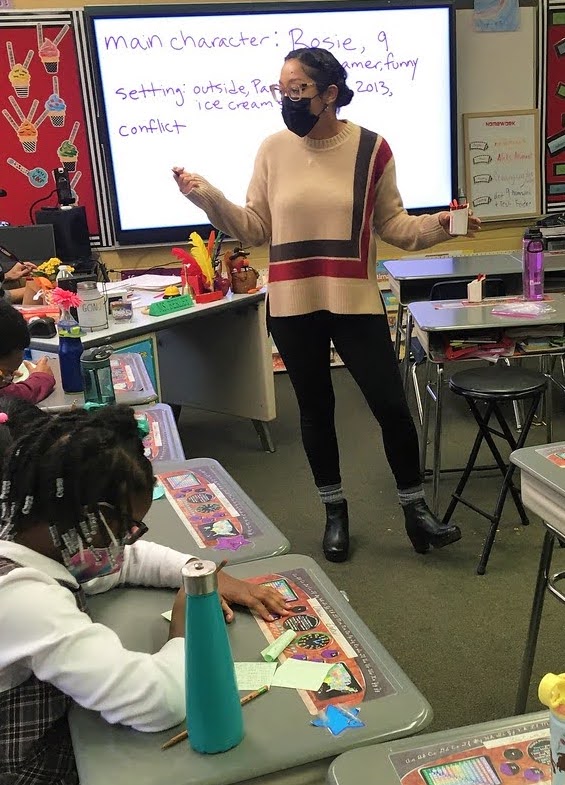

You started your career as a public school teacher. How did that experience shape you, as a person and eventually, as a writer?

Teaching public school gave me three gifts that I use a lot:

The first is time management. I think a lot of people who want to write spend a lot of time hemming and hawing about what’s the right setup to make writing doable. As a public middle school teacher, there were a lot of things that had to get done and no one was coming to do them for me. So you have to figure out time management.

The second gift teaching has given me is a direct sense of urgency—a lot of the things I write about are big and abstract, but those things play out in our lived experiences. Teachers deal with everything at the end of the line of social issues, from mental-health care crises to food insecurity. These are things that can feel huge and impossible, but these problems manifest themselves in the life of a child standing right in front of you who needs your time and care. It’s urgent.

A third gift teaching has given me is a premium on clarity. Middle schoolers are emotionally honest and direct. They can come up to you at any time and ask a question you can’t opt out of answering. I think it’s helped me be able to handle difficult, complex questions off the cuff.

What role did your upbringing play in how you view education?

I was raised by a single mom who worked really hard. She was amazing, determined, and brilliant. Having never attended college herself, she couldn’t lean on institutional support or a credential to get ahead in life, so she relied on relationships. I remember seeing Yo-Yo Ma play the cello on PBS. I told my mom that I wanted to play cello and she, somehow, got me lessons. She just always made it work.

My mom was very committed to making sure we had emotional safety and security, and joy, even when things were precarious. I value the simple stuff that she was super intentional about, like always feeding me breakfast at home at the kitchen table. It might have been a frozen waffle but it was that time together that mattered, because in the afternoon I came home from school to an empty apartment while she was still at work.

You’ve said that when you teach classes on education policy, you always start with the question, “What is the purpose of school?” The answers you’ve heard vary. What is yours?

There’s a difference between schooling, the institutionalized process, and education, the broader, transformative process.

In the United States, the purpose of school is to serve a political and ideological agenda. Whose agenda, ideology, and politics can be up for grabs. But the process of saying, as we do in America, that we’re going to have a compulsory educational system and designate state employees whose job it is to determine what knowledge is and is not important…that is inherently a political project.

So school is a political enterprise under the guise of “wanting what’s best for all kids.” But who decides? At some points and in some places that has meant, for example, hitting children if they spoke their native language in class, because somebody decided that only speaking English is what’s “best” for them. So “what is best” for kids should be the launchpad for a conversation.

Your latest book, Original Sins, has been described by writer Michelle Alexander as a book that will “change the way people understand the place we send our children for eight hours a day.” What themes have resonated most strongly with your readers?

I thought people would drill down on the tough historical details and want to talk about those things, but instead, people want to share their story with me, and the audience in the room, hear some insight, and ask, “What do I do?” People are seeking encouragement from me and from one another.

I couldn’t have anticipated the political moment when this book would be released. It’s a terrible moment for many educators. And yet, at my book events, more than half of the audience is often made up of teachers, and I see that they’re so committed to their students, and filled with courage and tenacity. I see that even in places that have been under very serious attack for a long time. The tone of the conversations has been about resolving towards collective action more than despair. That has been really moving for me.

The first chapter of Original Sins opens with W.E.B. Du Bois’s haunting question, “How does it feel to be a problem?” How has this question shaped you?

Du Bois is a really important ancestor to me. People fight over defining his disciplinary affiliation—a poet, a fiction writer, an artist, a sociologist. He was all of those things! And that gives me permission, as someone who works across disciplines, to do the same. I believe the most important thing is to pursue doggedly whatever question you have in front of you.

In your conversation with writer Fred Moten in New Suns, you spoke about embracing mistakes in music, language learning, and cooking—noting how important it is to continue on rather than stop progress when a mistake is made. How has this philosophy of learning through imperfection influenced your role as a writer?

This book took me five years to work on and it involved me integrating a lot of histories I knew really well, but in many cases learning along the way. One of the issues with social media is that it has created an environment where you want to express the one right thing in the one right way. It’s this idea that “being wrong” could be a career-ending moment in your life.

While I understand that fear, it stifles the opportunity to learn. So many of the best lessons in my life were in being in a reciprocal community with people who helped me learn from my mistakes. Transactional relationships can’t help you evolve. But trusted friends, colleagues, and mentors can hold you accountable and show you the way.

Let’s talk about power, specifically the power of narrative. You have described storytelling as having the power “to shift the conversation around something,” which you try to do in all of your work. How do you know when you have succeeded in that mission?

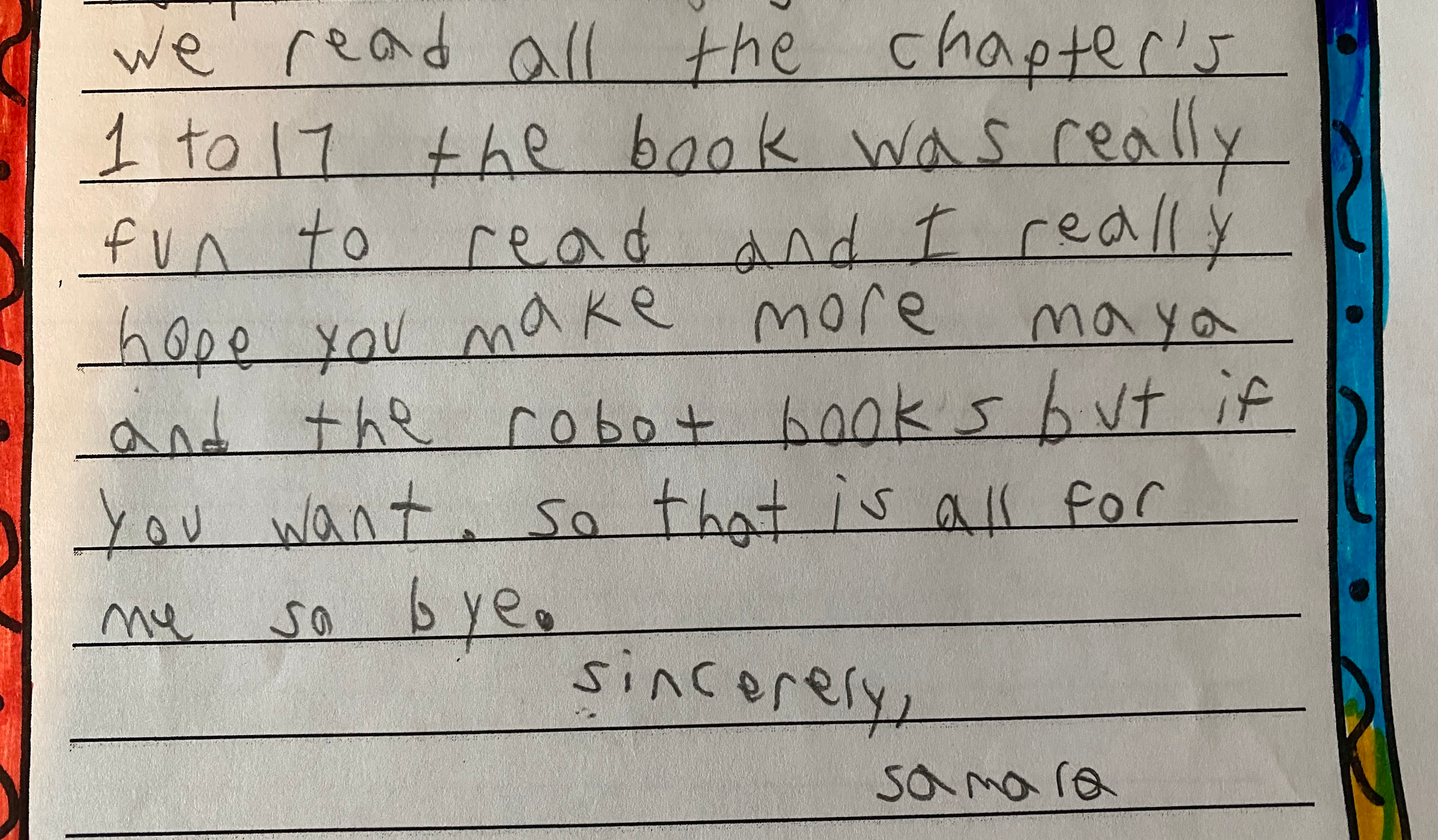

That’s a decades-long project and it’s done collectively. Everything that I write in a book is itself a representation of what people have poured into me. But I will say that books are very slow. It’s funny, in a sense, to commit to writing a book in a world where there are faster ways of communicating ideas, like through a podcast. But on this book tour, so many people have shared with me the impact of my last book, Ghosts in the Schoolyard, which was published in 2018. That book wrestled with the question about what is a good school and a good community, and who gets to decide what is “good.” So many people told me the book helped them understand their own role in history and how they fit in their community.

I did an event in the fall with Ta-Nehisi Coates and he said, “My books are brawlers out there in the streets,” and I know what he means—that books have a life of their own. I feel very proud that I’ve poured time into them and that they help give meaning to people’s lives—and sometimes I’ll know that impact and other times I never will. I found as a teacher that so often the student who says you were their favorite teacher is not always the person you would expect.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow