This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Your Fellows project will be a feature-length documentary film called The First Plantation (working title), examining the legacy of Drax Hall, the oldest continuously owned and operated sugar plantation in the Americas. You grew up in Barbados, just 20 minutes from Drax Hall, driving by it regularly. And yet, you knew virtually nothing about its history until a few years ago when you came across an article in The Guardian about the wealthiest landowner in the House of Commons inheriting Drax Hall. Can you describe your reaction to the article?

For as much as I knew of the history of Barbados, reading Paul Lashmar and Jonathan Smith’s article in The Guardian on Drax Hall floored me. I happened to be in Barbados at the time, and as soon as I finished reading it I closed my laptop, walked to the car, and drove straight to Drax Hall. I must have stood in that sugarcane field for nearly an hour, right until sunset, struggling and failing to fathom the history of the plantation and everything it’s wrought. I’m still processing it all. In many ways, working on this film is my ongoing reaction to everything I learned that day and continue to discover.

What ultimately led you to decide to include yourself in the film?

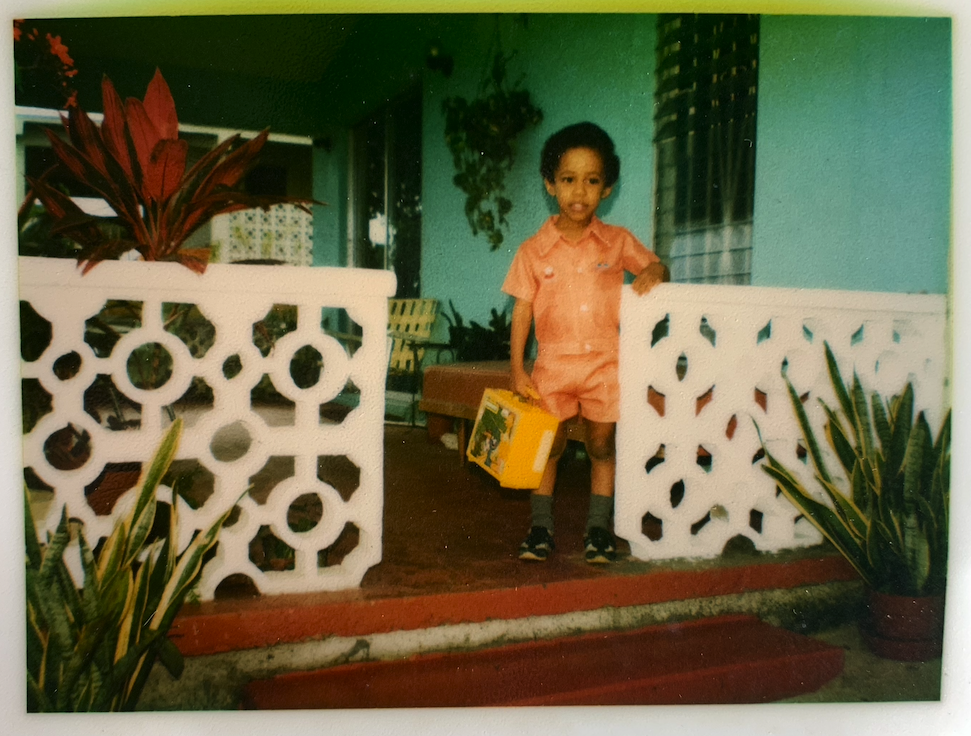

Originally, I was nowhere to be seen on screen, but as I had more conversations about the film with my crew, fellow filmmakers, and various funders, I gleaned their interest in what I had to say. I realized that so many of my direct, personal reflections on growing up in Barbados were worth including in the project. As such, rather than only focusing on the history of Drax Hall, the film now uses it as a jumping off point for my own spiritual investigation into the significance of Barbados’ history to both its citizens and the wider world, the relationship between chattel slavery and modern capitalism, and what it means to decolonize oneself. Finding the balance between something intimate and personally driven on one hand and something too navel-gazey on the other has required a lot of work, but it’s also been tremendously cathartic, allowing me to reach truths beyond what I initially thought possible for this project. The audience will be the ultimate judge of how well it works.

People might be surprised to hear that one of your biggest creative influences on the film has been Twin Peaks. Why is that?

I’m a massive Twin Peaks fan, but it didn’t occur to me until pretty deep in production that I was churning through similar ideas and feelings that the show stirred in me. Chief among them was the cognitive dissonance that arose from reflecting on the idyllic nature of the island and the ghastly history it conceals. It’s a dynamic that’s present in Twin Peaks, in which demonic, otherworldly forces swirl underneath a quaint northwestern town. My film isn’t nearly as bizarre as the show was at its best, but it’s still influenced how I contrast the horrific, lingering legacy of Drax Hall and the plantation economy of the 1600s against the image of the island as it lives in tourism brochures and the global imagination worldwide.

This project points to what happens when we neglect to teach local history in schools. What impact do you hope the film will have on Barbados’ school curriculum?

I have a deepening hope that this film encourages the Barbadian government to push forward on their stated plans to decolonize the island’s education system, which, in everything from its content to testing, still bears the mark of once being Britain’s favorite colony. There is so much that we were not taught about who we are growing up. We need to better understand our place in both history and the wider world.

What do you wish the public better understood about Barbados’ historic push for reparations?

I have great admiration for the activists and civic leaders who are driving Barbados’ push for reparations. Their campaign is quite thoughtful in how it addresses the island’s challenges in public health, education, technology, and climate change, and in how to support these areas beyond a mere payout. In fact, those on the frontlines of this issue believe a strictly financial conversation to be an insult, as there’s truly no sum that could repay the historic injustice that happened on our shores. Instead, they’ve constructed a reparative framework that will better help the island surmount the social, economic, and environmental challenges that lay ahead—challenges common to any developing, post-colonial nation with a fraught history that’s not of its own making.

You started your career as a beat reporter in Miami, describing your time at The SunPost as “a boot camp” that trained you for “turning stories around quickly” and “[latching] onto what makes people’s brains and minds and interests light up.” How have those experiences influenced you as a filmmaker?

My experience as a journalist at the The SunPost and later at The Miami Herald has come in handy in my filmmaking career, but has also presented unexpected challenges. What’s been difficult is defaulting on occasion to a hyper-literal mode, thinking of narrative in words and not primarily in image and sound. That said, leaning into that transition has also been the most exciting part of the creative process. On the flip side, my interviewing skills and research experience have really helped me dig into the most interesting and easily overlooked details of this story, and not a day goes by that I’m not grateful for my time in the newsrooms that shaped me.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.