This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity, and organized around key phrases in the conversation.

Begin with curiosity

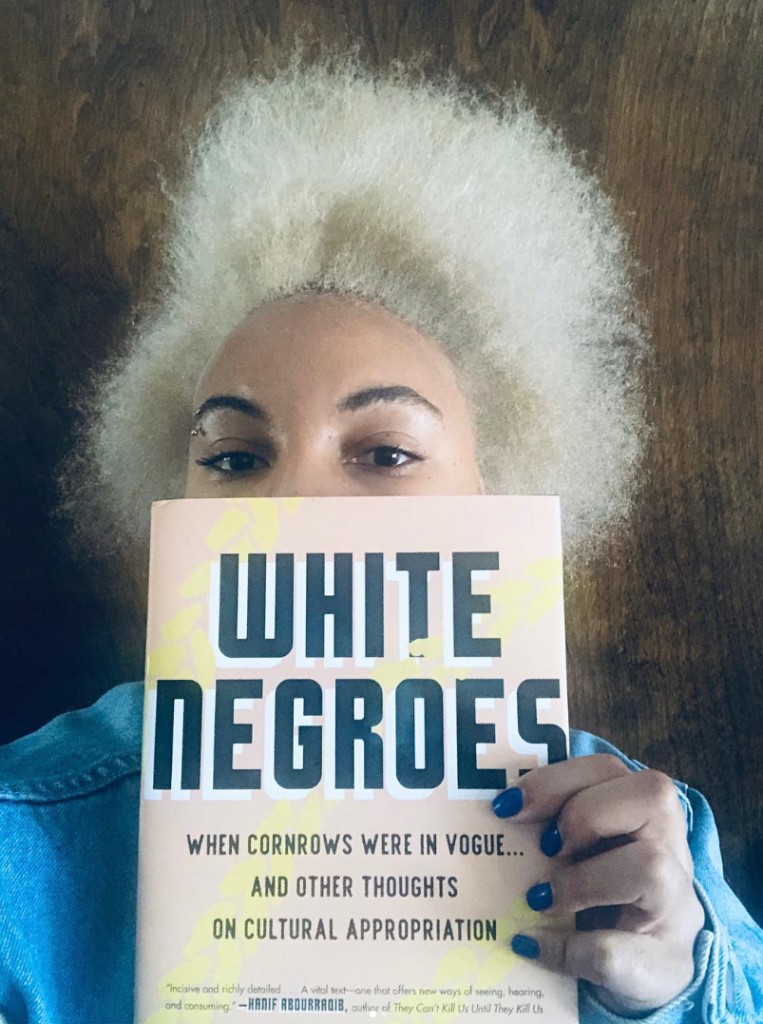

Before I started on my book White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue…and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation, the word appropriation was already somewhat codified in the national media as this fraught and punitive term. If you were a publicist, say, you would never want to see it associated with your artist in a headline. I’m always interested in the way that the terms we use are often taken for granted in their meaning—we say “appropriation” and we sort of pat ourselves on the back for knowing that it’s wrong and pointing it out when people are doing it. And yet we have innumerable instances, even in a recent history of mass culture, of what could otherwise be called appropriation that isn’t made conspicuous; meanwhile, more conspicuous occasions of appropriation, upon a longer look, take on a more convoluted appearance than a word like “theft” would connote.

I wanted to sit with both the conspicuous and inconspicuous and think about what is happening in a way that removes us from the easy narrative of here to there—as though every pop artist of the aughts woke up and thought, “How can I steal from a Black person today?” Culture has never developed like that and especially not in the age of the internet, where we are exposed to media that has been utterly detached from its environment. I like to begin with curiosity, because even if it leads us to some pretty dastardly places, as I think my book occasionally does, it still leaves us with a better assessment of the situation than the pointed finger.

In the classroom

Writers seldom get to observe the impact of how they see the world on others in a direct way—unless they are famous and/or especially didactic, or they teach. Teaching literature is quite direct and quite literal in its aims, making students read important (that is, relevant) works, and imparting methods that will help them in encounters with media beyond the purview of the syllabus. Sometimes I feel like my courses, if nothing else, give students permission to sit with a work of art and think—the sort of activity that makes life worth living and what the technologies governing their lives would rather they not. As a gift to them, I made an enthusiastic return to blue books a couple of years ago.

Who I write for

I always laugh when authors say that they’re not writing for a specific audience. I know what they mean—that they don’t sit down necessarily and stare at the computer thinking, this is for you Bobby from Springfield, Illinois, or whatever. Whereas, in truth, audiences are manufactured by the context out of which the work emerged. (I write for publications that fashion themselves for certain demographics that are not at all obscured but rather thought about by people above my pay grade.) And so, even as I would like to believe that my writing is available to anyone who happens upon it—and I do, often, choose to believe that—when I was writing White Negroes, I did imagine or maybe hope that I would tap into an audience of people who were caught by and even skeptical of this big fuss about the A-word.

I am feeling more comfortable in feeling less responsible for the audience, however minor, created by my writing, if only because getting misread often enough will disabuse you of the notion that you can ever control how people receive your work.

Kim Kardashian

In the essay “How Kim Kardashian West Came to Represent America,” I’m trying to think about Kim Kardashian as something of a cypher, whose presentation and reception says more about how race (and gender) is assigned and interpreted in the U.S. than it could ever say about her as a person, her individual subjectivity.

All celebrities are surfaces, and I admit I find her surface interesting. It’s very canny to the workings of race in America, and I think we know that, even as we resent her for it. The Kardashians slim down and lighten up, and the public reads this as auguring the return to aping a certain WASPish whiteness; maybe the video vixen, the WAG, is over. They function as a sort of racial bellwether. How can it be an accident that Kim is playing around with Tesla robots in a time of flagrant techno-fascism?

Being a professional critic

Preconceptions make you sloppy. They make you overlook things that shouldn’t be overlooked. I don’t even necessarily mean that in a “don’t judge by the cover” way—usually people say this as encouragement to be open to the idea of liking something. Whereas, I might have a sense that I’m probably not going to like something and will be correct that I don’t like it, but nonetheless need to be able to perceive how the thing is putting itself together so that I can describe what isn’t good or working. And that’s easier said than done.

Surviving in media

I don’t enjoy giving blanket advice, but what tends to apply is that the best shot in this [writing business] is to get really, really, really good. That does not mean that everyone who has a job—in academia, media, or otherwise—is good at it, and that does not mean that everybody who is good at it will get a job, far from it. But the faith that cannot sustain is that going through the motions will yield something solid. The people who can sustain that sort of faith have been earmarked since, like, birth, and know who they are. For everyone else—a shot in hell is going to take so much work. So much writing and writing when you’re not being required to write, writing whenever and wherever you can, and reading and reading, so so much reading—reading the people alongside whom you want to be published, reading trade books and academic books, reading weird little books, reading people who are way smarter than you, who are way better writers than you are, reading people who are unpopular but brilliant.

But really, there is absolutely no shame in getting an “email job” that is going to give you health insurance so that you can survive long enough to write the things that you want to write. Just don’t work for a weapons manufacturer.

The internet broke my brain

There’s a tweet that used to haunt me, it went something like: You can tell when a writer is very online because their writing is always guarding against strange counterarguments that normally nobody would ever bring up. It’s the curse of the person who says you hate pancakes because you said you like waffles, and also the curse of Galaxy Brain, the grammar of social media—in which the thing that everyone says is bad is actually good, or is still bad, but is bad because it’s good in this way that nobody’s talking about. And on and on.

It’s hell for writing. My worst pieces suffer from this sort of thinking. And on one hand, it seems like less of a concern as social media platforms become less usable as a means of reading anybody’s pulse on any given subject. Yet with the increased usage of LLMs [large language models] and mass influx of slop online, people seem to be growing even less concerned with sourcing the media that is shaping how they express themselves. [The pursuit of] engagement and attention, such as they incentivize shedding attribution for ease of circulation, has a bad effect on the work. Everything has to be direct and to the point, and made for easy reading [to be shared on social media]. And the writing is worse for it.

July 9, 2025

Photos provided courtesy of the Fellow.