This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

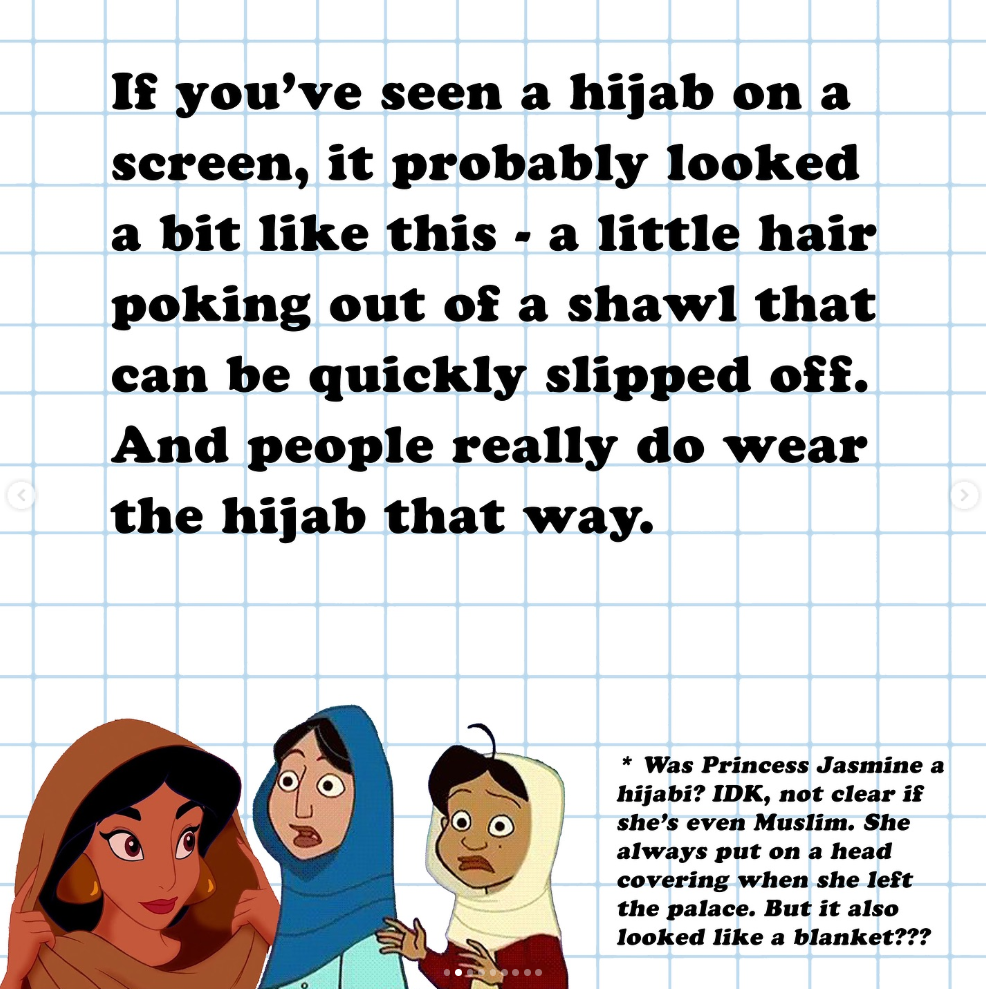

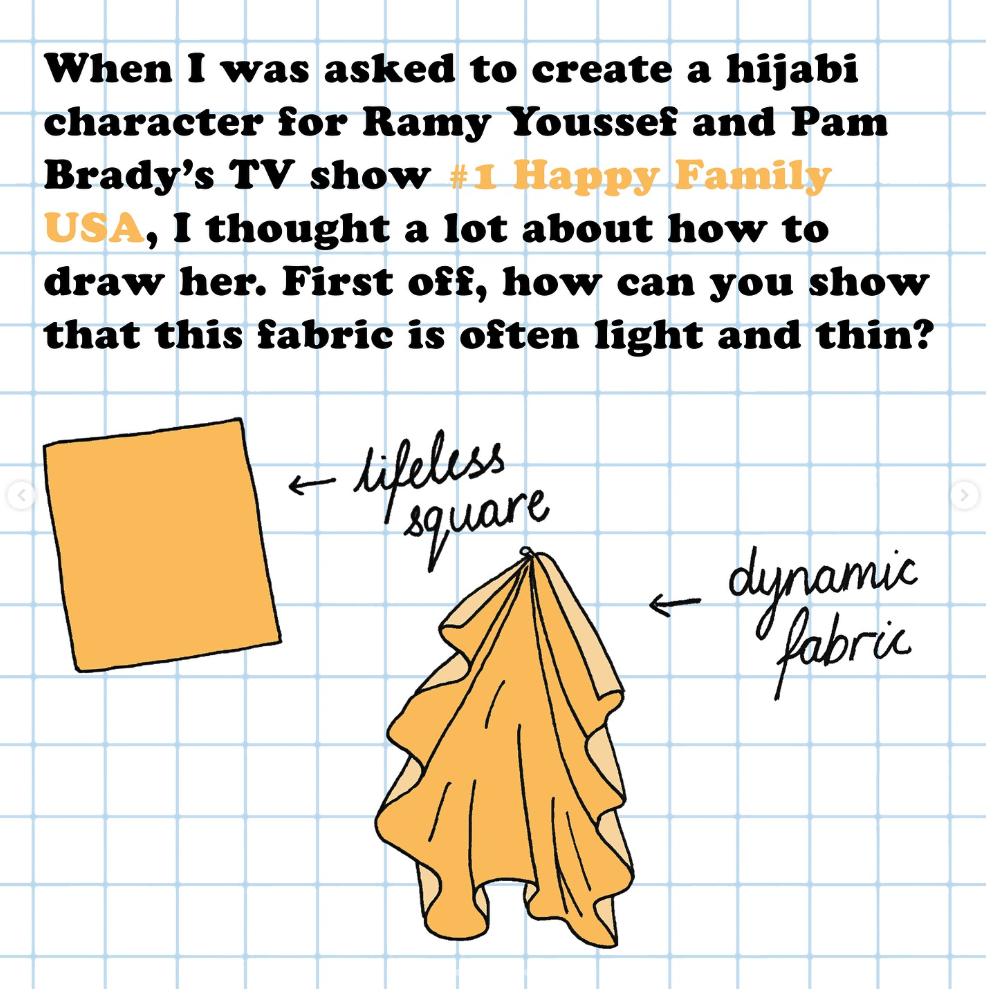

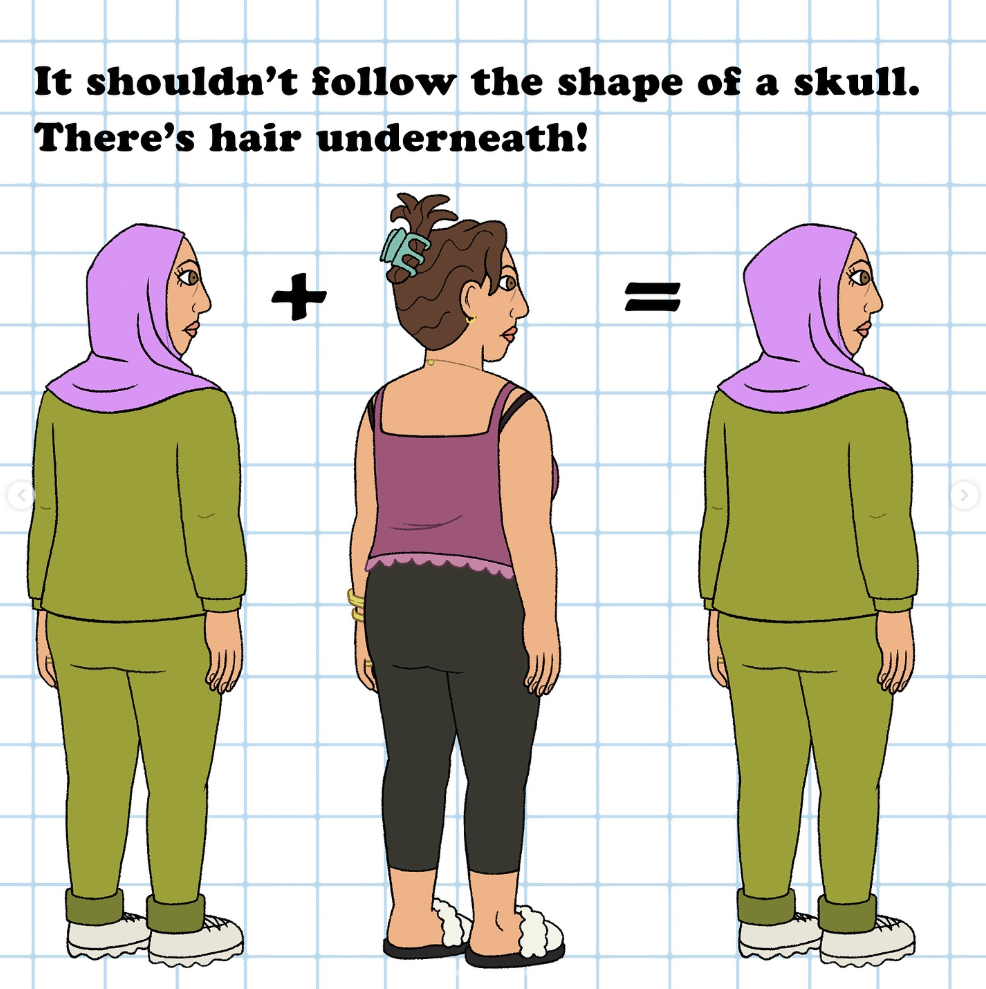

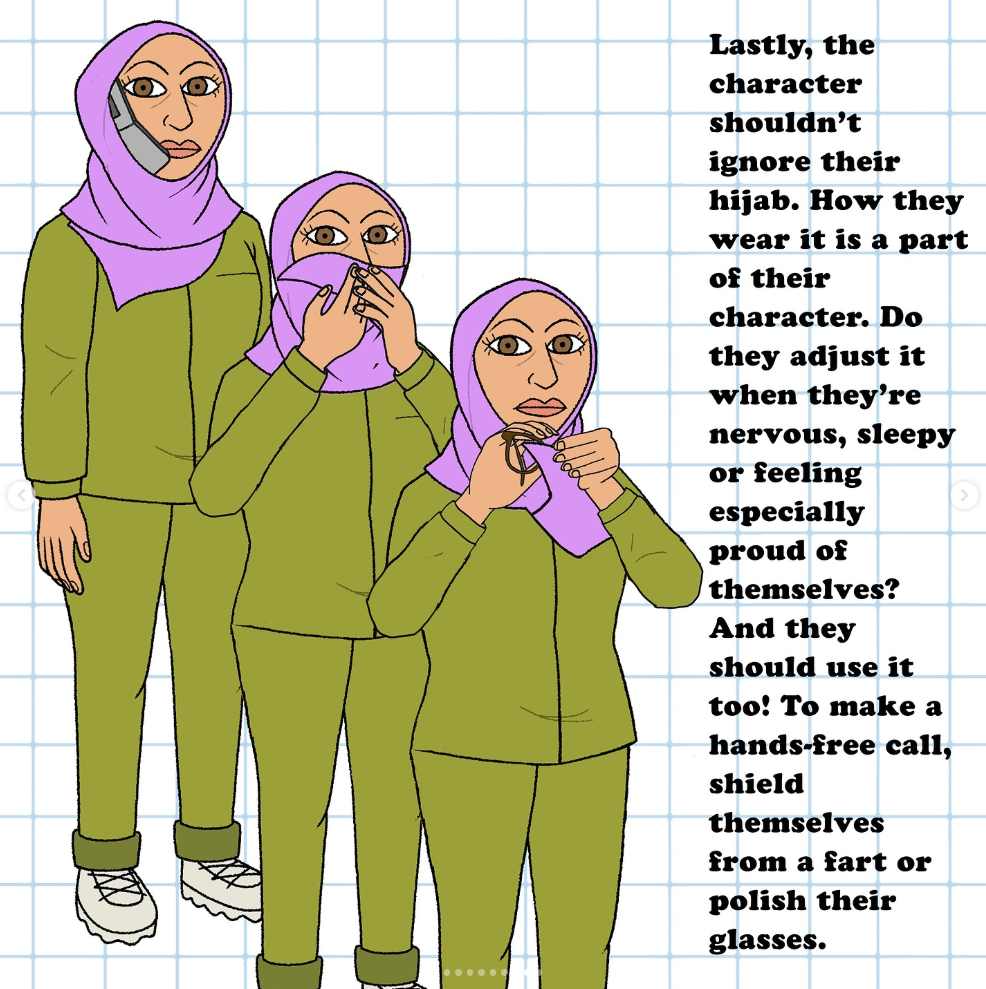

You created Sharia, the hijabi mom character in #1 Happy Family USA, the first time a main character in a U.S. animated series has been shown wearing a headscarf. You gave tremendous thought to how you could illustrate that “the hijab isn’t just an outward expression of inner values. It’s as practical and fashionable an item of clothing as any other.” What reactions have you heard from audiences so far?

I feel so grateful because the reaction has been so positive. I literally haven’t heard anything bad—and that’s virtually unheard of!

From the get-go, I wondered if I was the right person to create Sharia because I’m not hijabi. And so, it was so nice that people who wore hijabs said that Sharia’s depiction was good and that what I created meant a lot to them.

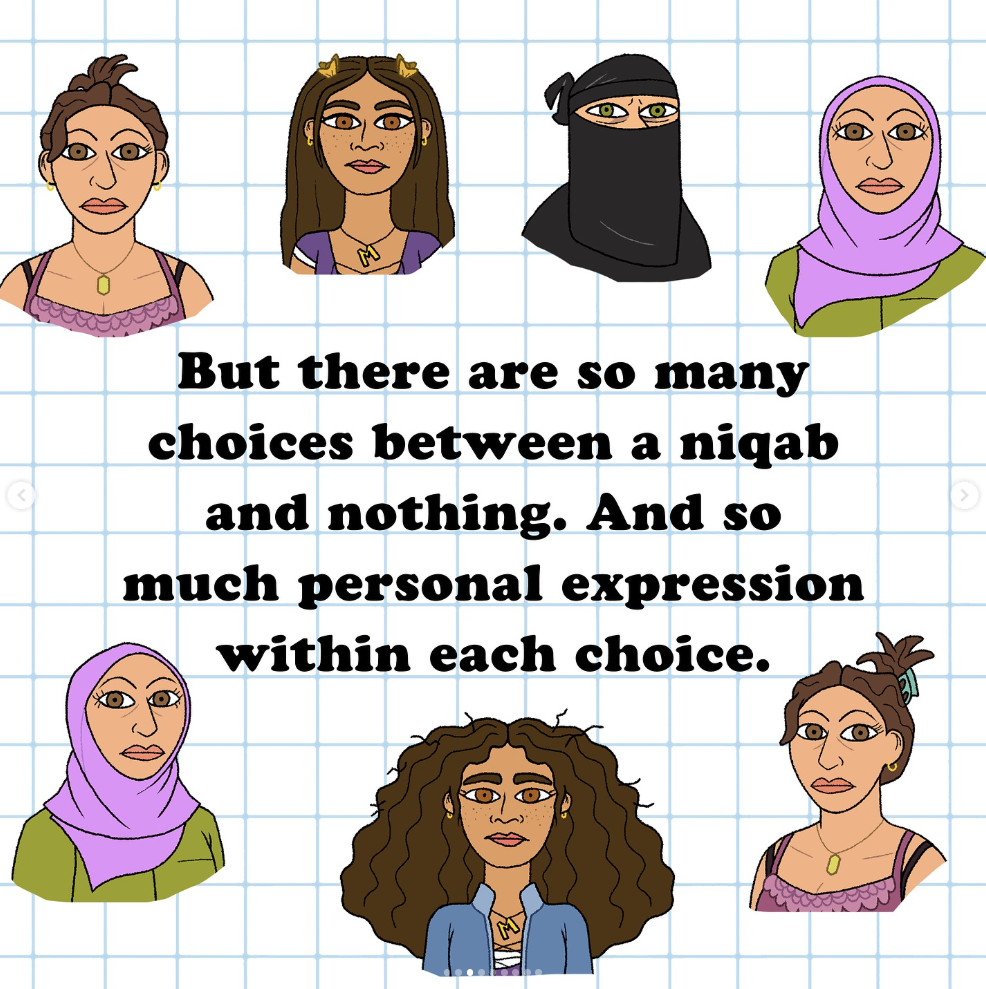

I approached this project with a lot of humility. I didn’t say that this is the definitive depiction of a hijab. I wasn’t talking about religious or scholarly interpretations of the hijab. The hijab means different things to different people, and actually, it can have this levity to it. It can be this thing that you want to accessorize and feel beautiful in, as well as this piece of clothing that has enormous significance to you, too.

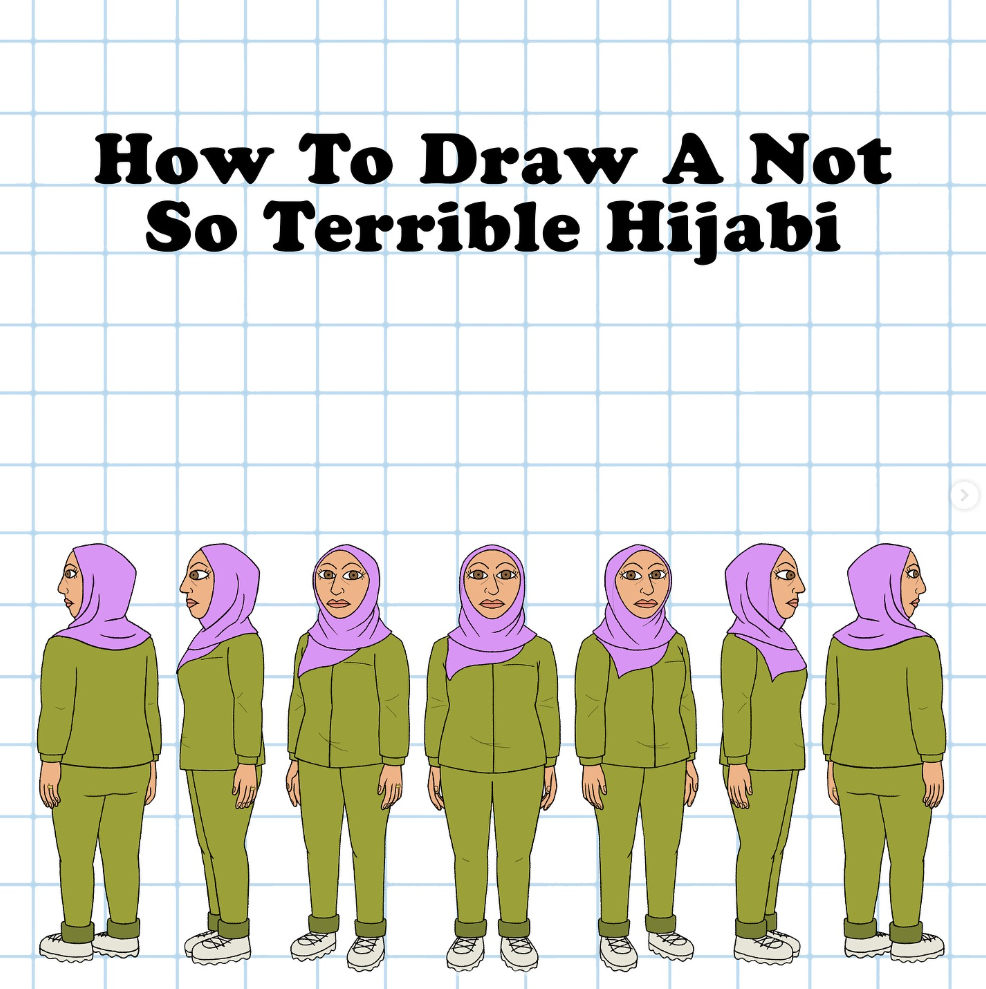

“I loved drawing this character because I love who Sharia is—her obstinance, her sense of humor, her courageous quest to solve the murder of Princess Diana. I hope I did her justice, especially because she’s the only main character wearing a hijab on US tv right now.” —Mona on Instagram

Along the way, I showed the co-creators of the show, Ramy Youssef and Pam Brady, working illustrations. Pam is a former creative producer for South Park, so she has a wealth of experience in animation. She talked about the practicalities of the character. She explained that the character’s head needs to be massive in proportion to the rest of their body because otherwise you don’t see the expressions well on their faces, which I thought was really interesting and also hard because I wanted less cartoonish energy, and a big head and big eyes contribute to that look and feel. So, we went back and forth, and I saw exactly what she meant, and I think the characters are better for it.

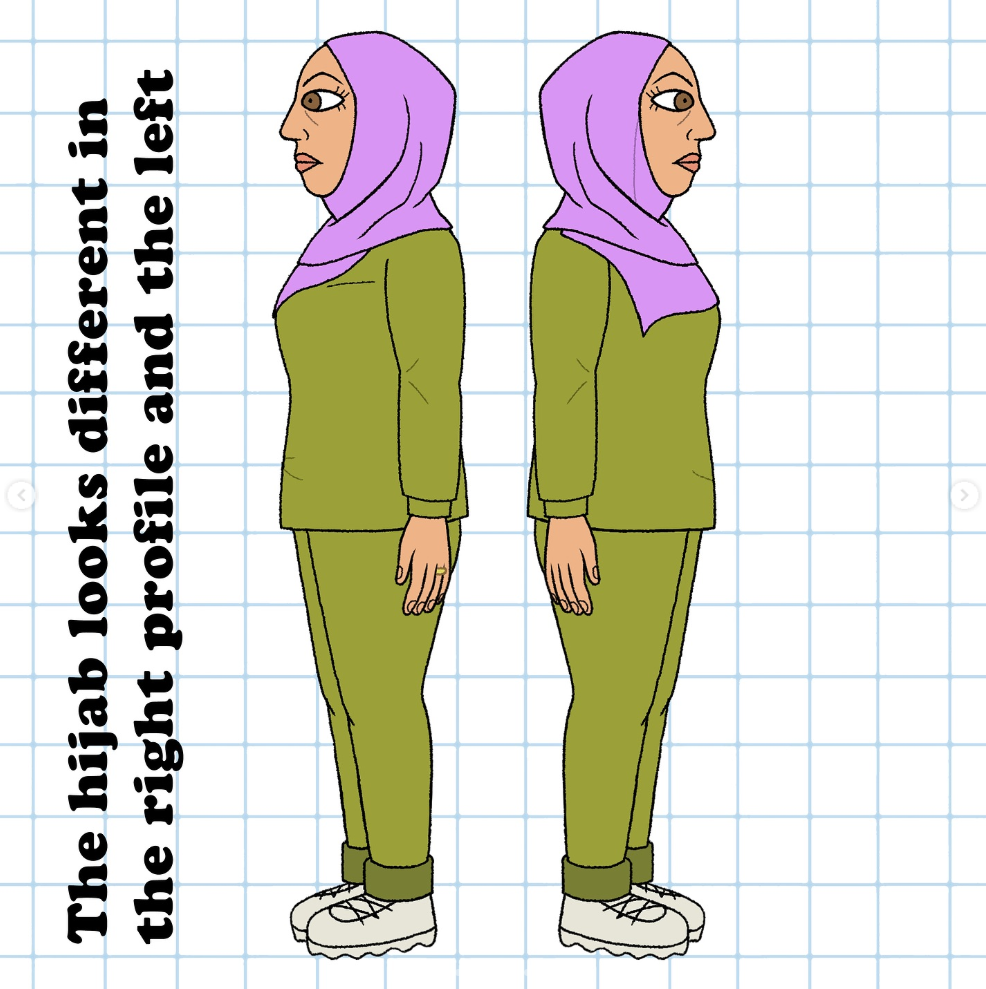

The team that I worked with was vast—nearly 300 people—and one of the most incredible was Kendra Melton, who worked on character designs and what are called “character turns,” which is how you show the character from all different angles. And also, having a very large team means there’s a ton more negotiation, but it’s so much less lonely than journalism, and the process is more collaborative. I could feel myself getting sharper just being around so many creative ideas.

Can you talk about the colors you chose for Sharia’s character?

So often, the hijab is depicted as quite drab, as if women want to erase themselves. And that’s not been the experience of my family at all, where many of the women wear hijabs. I just met my cousin in Los Angeles and she walked into the coffee shop wearing all leopard print and a straw hat on top of her hijab. I mean, after all, it’s clothing, it’s an expression of who we are. I chose pink and green for Sharia’s character, in part, because I love that combination together. I also see Sharia as a militant feminist, so green is an allusion to that part of who she is.

In a review of #1 Happy Family USA, the writer Aymann Ismail describes watching the show as not just cathartic but necessary: “It reminds some viewers of a moment we never got to narrate and gives us the chance to enter it into the record. It doesn’t ask Americans to see Muslims as more fully human. It asks Americans to sit with how ridiculous and dangerous their fear was, and still is.” How does that resonate with you?

It’s absolutely spot on.

I did not think when I started working on the show that it would be as relevant as it is today. We got the green light in 2020, and it’s finally been released in April 2025. The process took so long because that’s the nature of animation. From the moment I was attached to the show to the time that we had the main cast of family members took 10 months. I felt like an incredible failure! But someone more experienced in animation said that it usually takes a year to 18 months just to finalize a cast of animated characters.

You’ve said that your approach to using data in storytelling has evolved—especially in terms of pacing. In one interview, you reflected, “Five years ago, I was trying to do a piece in a few hours the day of, and now I’m just like, no, I’m going to take a few days and I’m still working the same number of hours each day. There’s no change in the intensity, just a more cautious approach.” How has that slower, more deliberate pace changed your creative process, and the work you produce?

Getting older is definitely a part of it. The point is not to be first; it’s about getting it right. Even when I was young I felt that I had only so many years of this energy—and that was part of my desire to break my back at work, because I knew I had a limited time to do so, and that time has now ended for me. I’m not willing to sacrifice my physical health for the end product. I’ve just slowed down. And what’s funny is, I realized that the many articles that I don’t end up writing and the illustrations that I don’t end up doing—it’s fine. The ones that are really, really worth it are the ones that you cry over, the ones you put to one side and they just keep coming back up—whether it’s at a dinner party conversation or they emerge just as you’re about to go to sleep. Those are the ones really worth doing.

Your Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times Magazine piece, “9 Ways to Imagine Jeff Bezos’ Wealth,” manages to surprise—and even, at times, delight—the reader. How do you strike a balance in tone? And what role does humor play in your work?

I think humor is a really, really important tool in a journalist’s toolbox. Part of our role is to present information in a way that is, first and foremost, accurate, but we also need to offer it in a way that doesn’t make people look away. When you’re writing about very serious subjects, the question is: How do you grab the reader’s attention and inform them? I recall working on an illustration about data released by the World Health Organization about the lingering symptoms of COVID. I wanted to educate people about the virus and also make sure that what they learn, they remember. So, how do I do that? It turns out that one of the lingering symptoms of the virus is diarrhea, so I drew a person clutching their butt. Now, that can look a bit silly, but so many people commented on that one visual! And look, it’s really important information from a public health messaging perspective. It helped people recall one of the core symptoms of lingering COVID.

So much of journalism is informing people of things they don’t know. In the case of Jeff Bezos’ wealth, I started on that piece from the premise that everyone knows he’s very, very rich, and we’ve become desensitized to it. My role is to make his net worth surprising to you all over again. It’s not the exact figures that matter; it’s his vast fortune versus the income of the average American. This enormous wealth disparity results in political power and this new fascism in America.

I spend as much time working on the language of a piece like that as I do on the illustrations. I want to make the language accessible—so, I’m constantly asking myself, am I using the simplest and most accurate words to describe this problem?

July 9, 2025

Images provided courtesy of the Fellow.